Dec 3, 2010 | Art, Travel

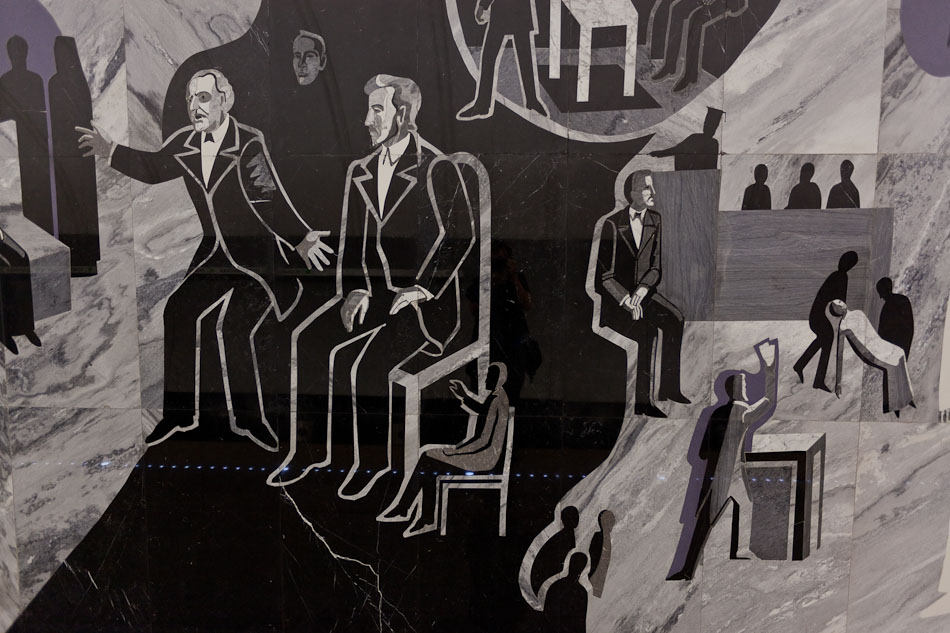

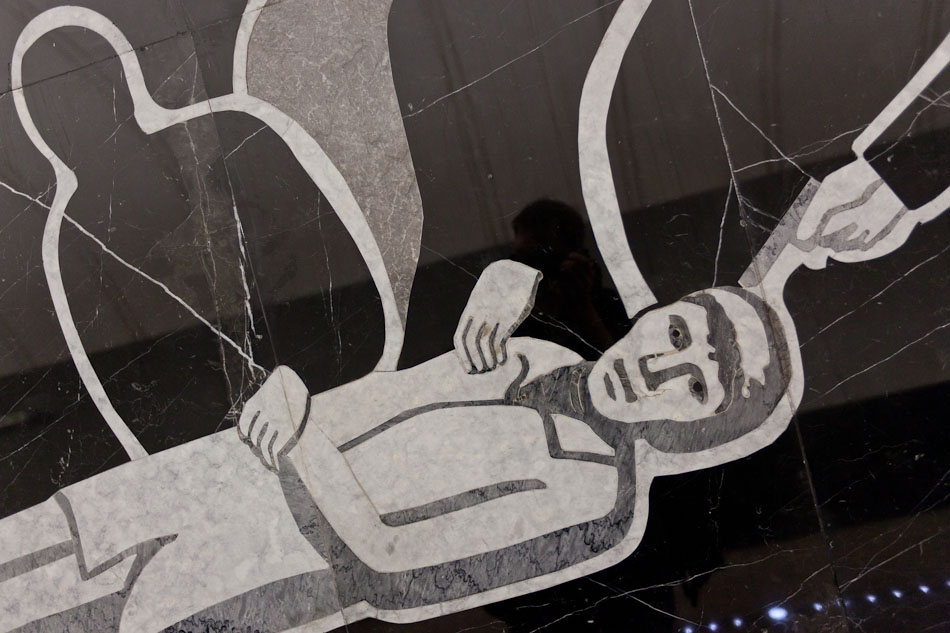

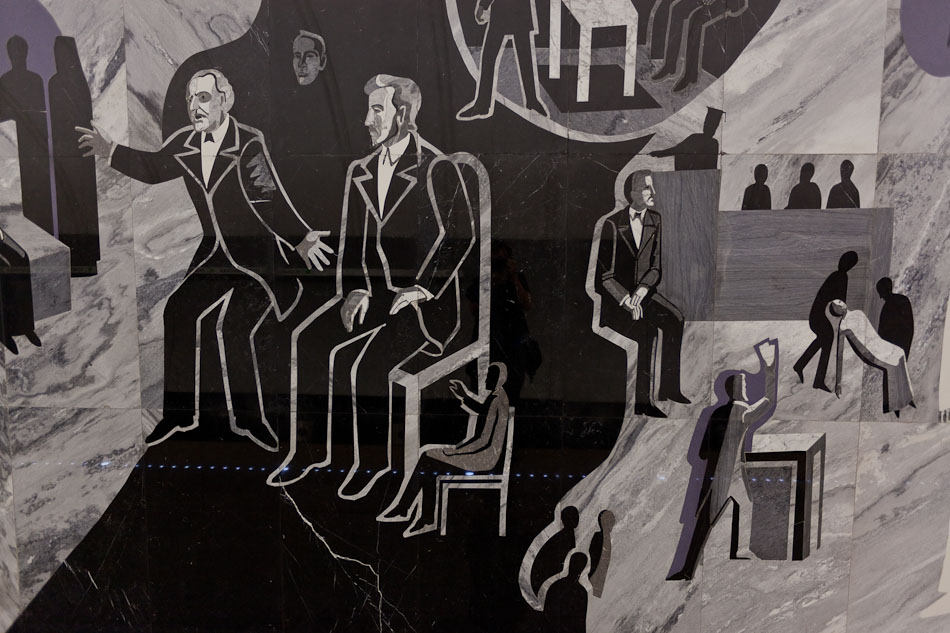

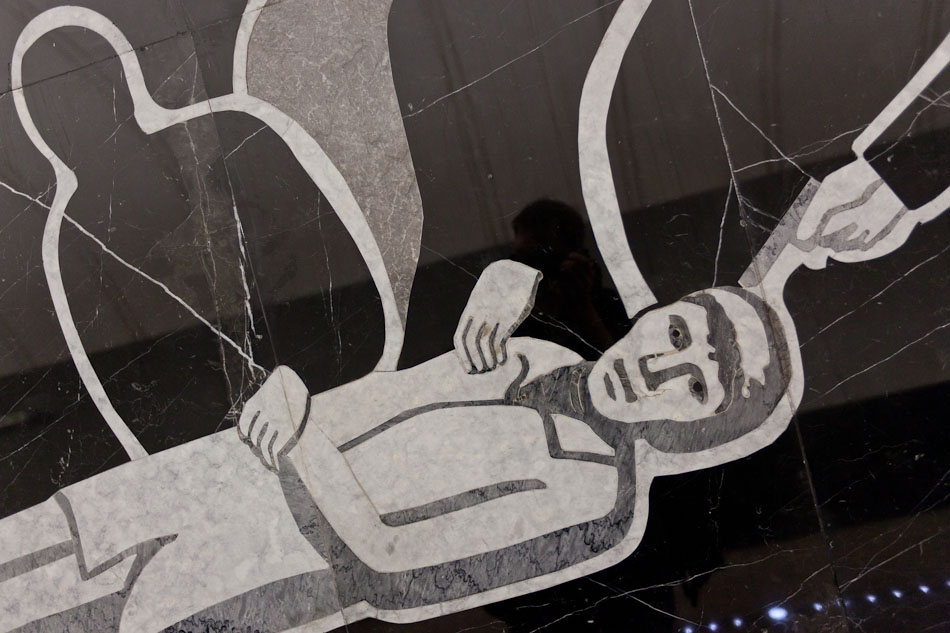

Moscow bears the historical stigma of a brooding city fringed with murder, corruption and greed. Now these grim trappings of the Russian psyche have found a home underground. The Dostoevskaya Moscow Metro station, named in honor of Russia’s dark prince of literature, delves into the most gruesome nooks of Dostoevsky’s oeuvre. The graphic nature of the murals even went so far as to delay its opening earlier this year. A prominent Russian psychologist, Mikhail Vinogradov, declared before the unveiling, “The deliberate dramatism will create a certain negative atmosphere and attract people with an unnatural psyche.” There is no doubt that death hangs heavy over the polished marble of Dostoevskaya with depictions of Raskolnikov wielding an ax against an elderly pawnbroker and her sister from Crime and Punishment and the suicide-obsessed Kirillov holding a gun to his head from The Demons. Concerned Muscovites fear the station might become a magnet for those contemplating suicide, adding to the almost eighty committed on a yearly basis in the Moscow Metro. However, after my own visit, I felt such concerns are unwarranted. The entire station inspired a sense of reverence and awe. I felt like I was meandering through a church instead of a public transportation hub. The aura of Dostoevskaya was only punctured when a train screeched into the station and let off another teeming load of commuters. The artist behind the murals, Ivan Nikolayev, remains rightfully unapologetic, “What did you want? Scenes of dancing? Dostoevsky doesn’t have them.”

Apr 11, 2010 | Society

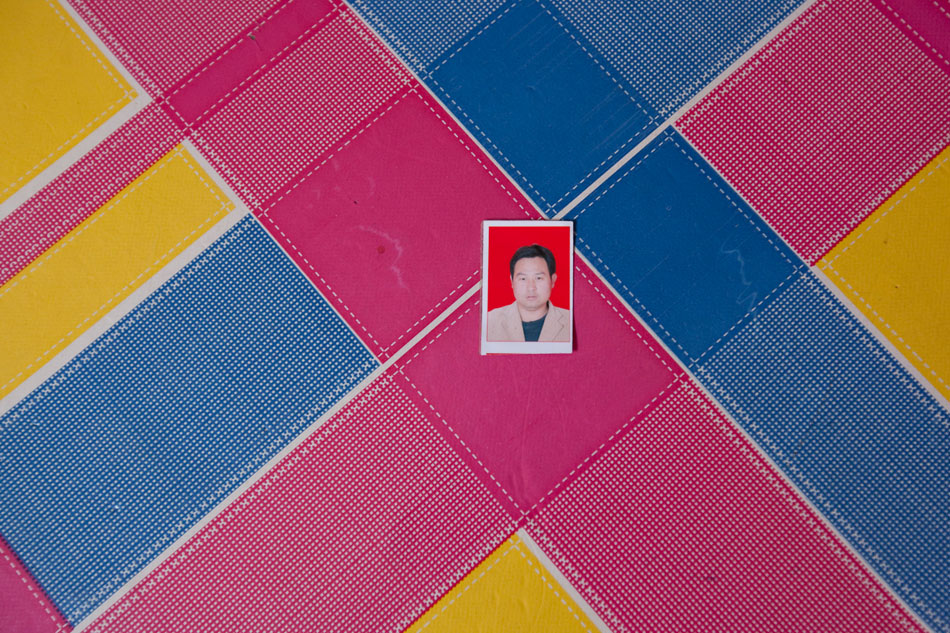

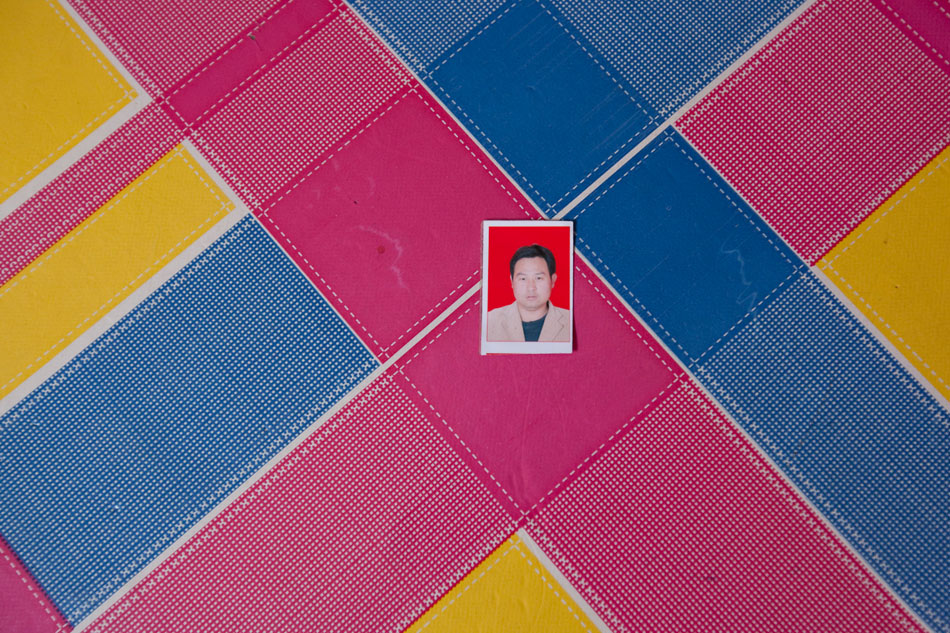

This past weekend I embarked on a very intense assignments. Working with the potentially bereaved wife of a Shanxi coal miner, Shi Weike, only a week after a major mining incident was delicate work to say the least. Shi Weike moved between different jobs in rural Shanxi before taking up the dangerous but relatively lucrative position as an electrician in the Wangjialing coal mine. Coal is big business in the mineral rich but relatively poor province and provided Shi Weike with steady income to support his wife, Guo Qinqin, and daughter, Shi Rongrong. However, on the morning of March 28, the main shaft of the Wangjialing coal mine flooded when workers accidentally broke into an abandoned shaft filled with water. Although over a hundred miners were miraculously rescued over a week after the flooding, the fate of Shi Weike looked dark as the government still refused to list the names of the survivors and deceased. His uncle, Yang Shirong, faced the task of consoling Guo Qinqin who after two-weeks of waiting is began to lose hope for her husbands’s survival. Every day she stayed in bed and took an intravenous glucose drip due to her inability to eat. Shi Rongrong, her six-year-old daughter, was also not informed of the possible loss of her father. Like many other coal mining families Quo Qinqin will now have to seek compensation from the government in order to support her family. Coal miners die on an average of seven per day in Shanxi as safety regulations continue to be overlooked across the province. Taking the photos of Guo Qinqin on her mourning bed was one of the toughest things I have had to capture in my life. You can see the article and slideshow online at the Wall Street Journal website.