Aug 27, 2012 | Clippings, Development, Urban, Visions of Modernity

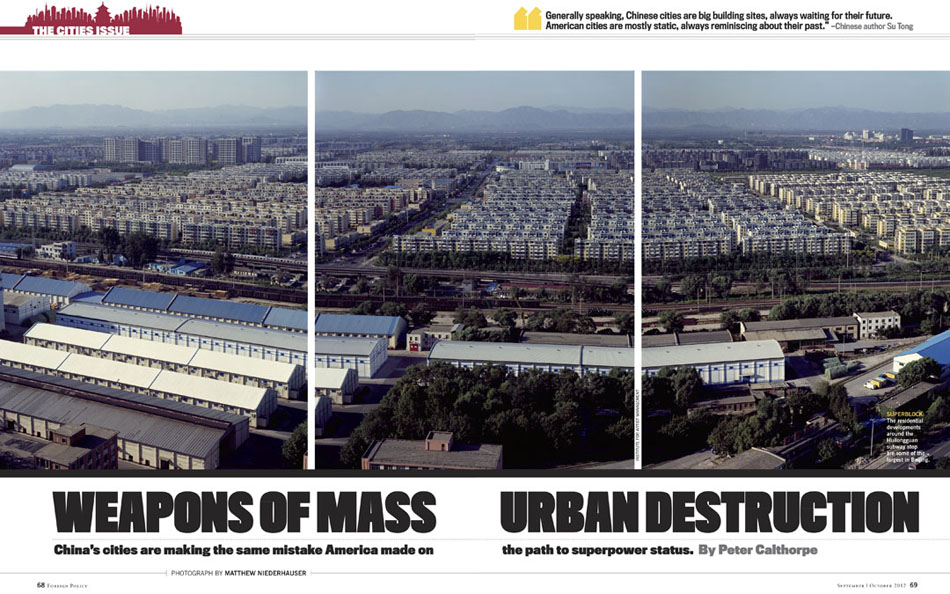

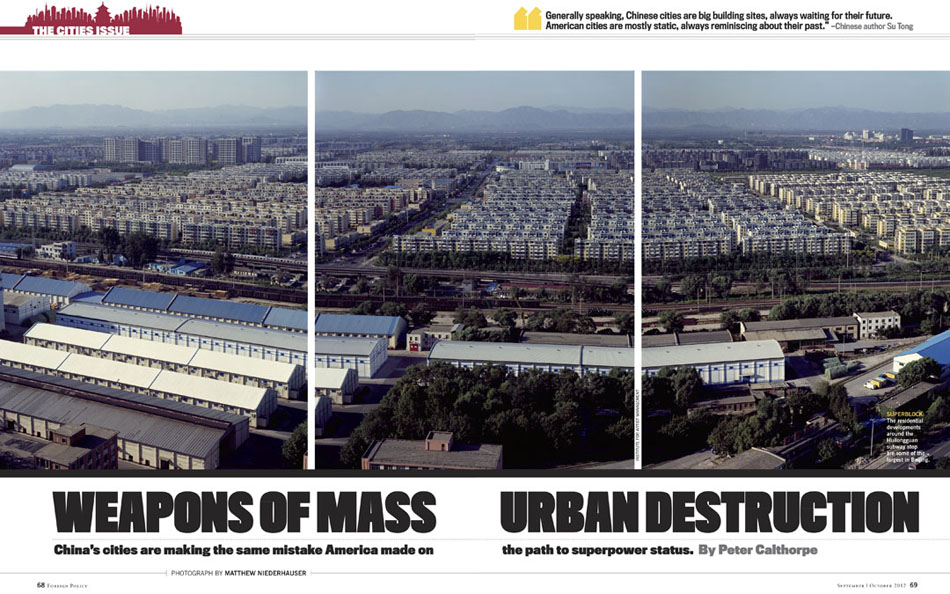

Foreign Policy’s current issue on urban development focuses almost exclusively on China. Relying on research by the McKinsey Global Institute, the magazine delves into the 75 fastest developing metropolises on the planet, 29 of which are in China (Shanghai and Beijing top the list, respectively). It is well worth perusing the actual magazine, which features photographs from my Visions of Modernity project, and delves into the serious ramifications of China’s ambitious infrastructure projects. Many of these unprecedented developmental efforts appear more and more misguided. My panorama of clustered residential developments surrounding the Huilongguan subway stop in northern Beijing, seen above, accompanies a piece entitled Weapons of Mass Urban Destruction. The article investigates many of the issues I explore in Visions of Modernity, the foremost being the unsustainable nature of urban planning in China and how it effects consumer, transportation and leisure habits.

The Foreign Policy website also features a series from Visions of Modernity where I documented Ikea customers in Beijing who partake in leisurely afternoons settling into faux showrooms scattered throughout the store. Each photograph suspends the shoppers in their appropriated Ikea environments, as if they were in their own homes. Such nascent nesting and consumer habits are catalyzed by the proliferation of individualized apartments in towering residential developments. These are known as megablocks and have become the cornerstone of Chinese urban planning. The monotonous and imposing structures dominate metropolises across China, forming urban islands that extinguish any sense of fluidity within cities. Although Foreign Policy delves into transportation and architectural projects that give some cause for optimism, such stratagems simply don’t exist on a scale to keep up with the massive urban migration China is experiencing and the concomitant demands on natural resources and energy. In many ways, I must agree with Ai Weiwei’s dark assessment of the plight of China’s cities. It can all seem very bleak. More panoramas of Beijing from Visions of Modernity are below.

Aug 28, 2010 | Architecture, Clippings, Development

It seems that my recent photo essay on Chongqing for Foreign Policy is getting mixed up with a surge of attention focused on the fastest growing city in the world. Both James Fallows and Wired’s Raw File mentioned my work, and there is another excellent piece posted by Caixin entitled Chongqing’s Call to Urban Conversion. Chongqing is easily one of China’s (if not the world’s) greatest experiment in urbanization. How these fledgling city slickers decide to dwell in their newly minted megablocks will set new precedents for living standards across western China. It’s going to be interesting to see whether or not such rampant growth will hit a wall by 2020 when the population of the city center is supposed to reach up to 20 million people. Also, see fellow INSTITUTE artist Nadav Kandar’s photo essay Yangtze, The Long River – easily some of my favorite imagery of the beast that is Chongqing.

Oct 24, 2007 | Development

The #5 subway line was all the rage when it first opened earlier this month. Locals lined up for blocks to catch an inaugural ride on the latest edition to Beijing’s underground. Although initial excitement soon subsided, people’s expectations for more and better transit options reached new heights. The slick #5 subway cars sported flat screen monitors displaying local news, spotless interiors, and exacting temperature control. The antiquated #1 and #2 subway lines still run on time, but now stand out as the ugly stepsisters of Beijing’s expanding public transportation system.

The opening of the #5 subway line also reshuffled Beijing’s suburban housing market – everyone wants to live next to a subway line these days. Traffic congestion is without a doubt the largest drawback stemming from recent surges in urban wealth and population density. Beijing’s newfound love affair with the car might come to a grisly end if traffic levels continue to rise at the current pace. Nobody can escape the mind bogglingly clogged expressways after 5PM. I would rather shoot myself in the foot than face such a cataclysm on a daily basis. The northern terminus of the #5 subway line thus stands to become the newest haven for low-income workers looking to escape increasing housing prices in the city center while maintaining a relatively short commute.

Picking an appropriately dreary afternoon, I headed out to investigate the new residential developments at the end of the #5 subway line. The area in question encompassed the last three subway stops and bore the unsettlingly kitschy name Pathway to Heaven Gardens (天通苑). If your idea of paradise includes high-rise concrete housing blocks arranged like a precarious domino set, look no further. These hulking domiciles symbolize the pinnacle of China’s insipid community planning; even the grassy fields surrounding the development appeared devoid of life. Only the occasional movement of tenants scurrying in and out of the complex lent a breath of vitality to the concrete jungle.

The only redeeming value of the area was the people living there. I stuck out like a sore thumb and soon struck up a number of conversations with inquisitive locals. My favorite included a gang of young security officers from Hebei Province skirting their duties and hanging out underneath the end of the of #5 subway line. They were happy to have jobs in Beijing but found the community lacking the warmth of their hometowns. It’s not hard to imagine such difficulties would occur within the migratory population, but their living environment did nothing to establish new bonds between the residents. I plan to revisit this area throughout the year so expect more reports concerning the Pathway to Heaven Gardens.