Oct 7, 2010 | Architecture

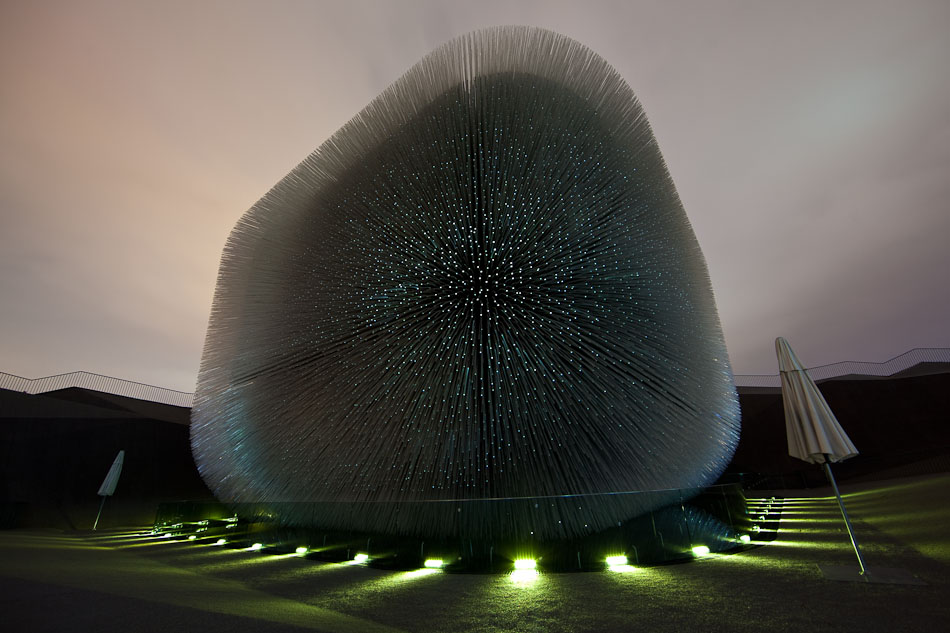

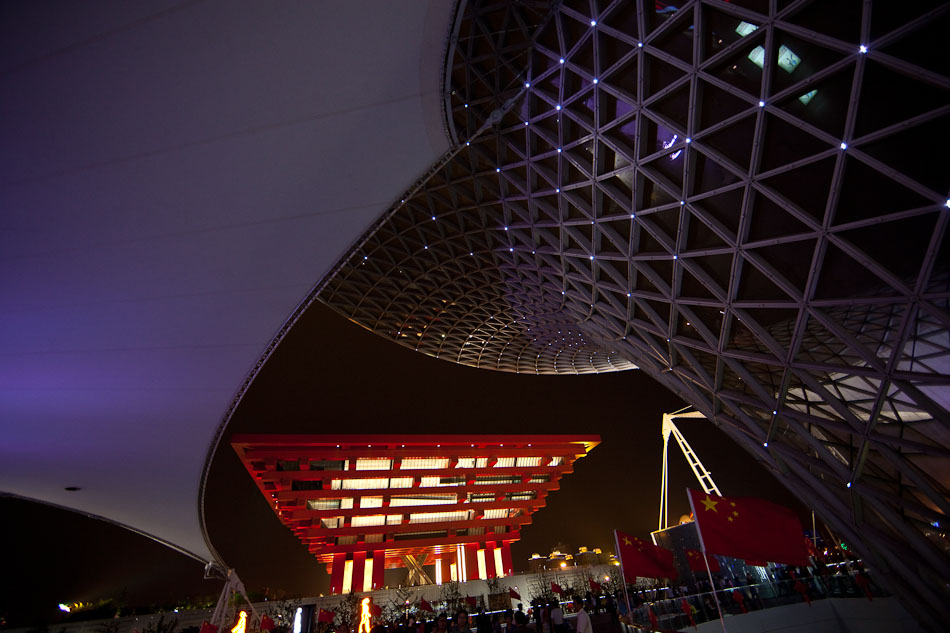

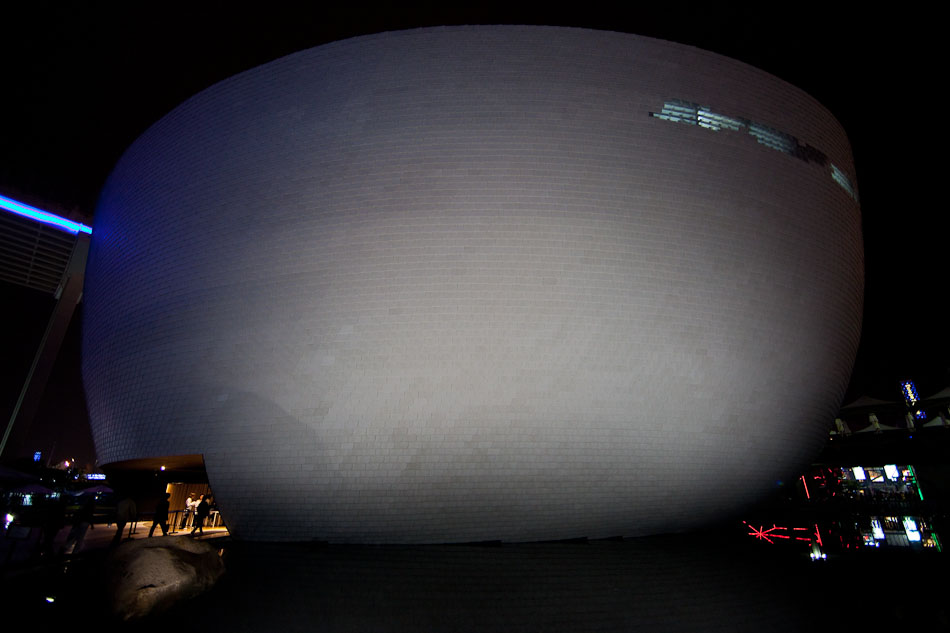

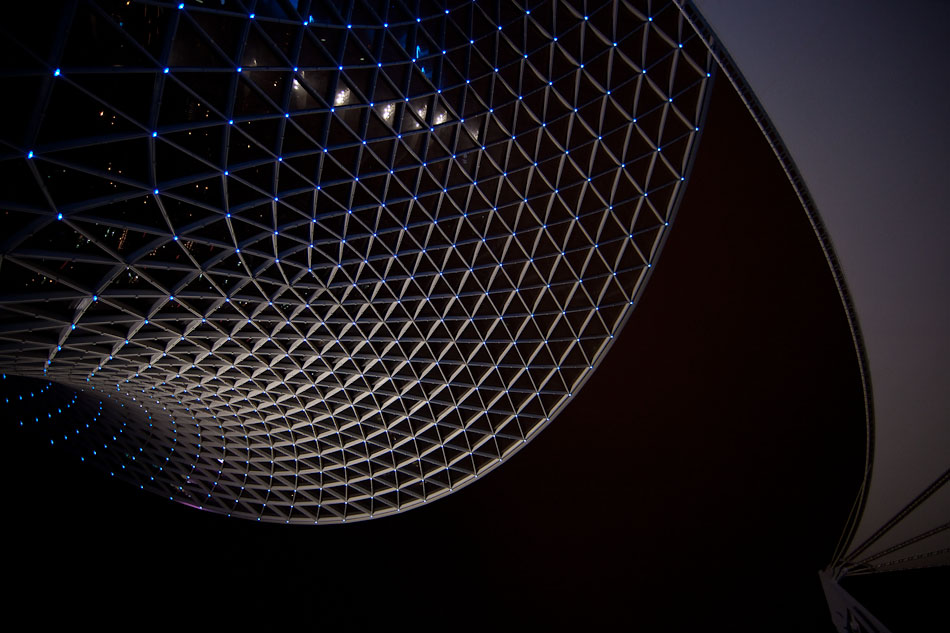

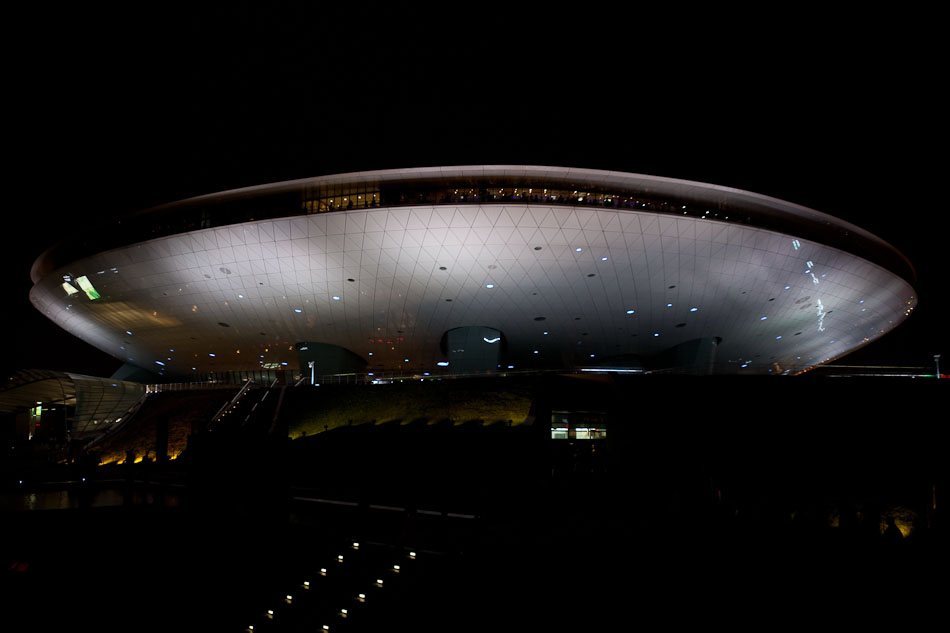

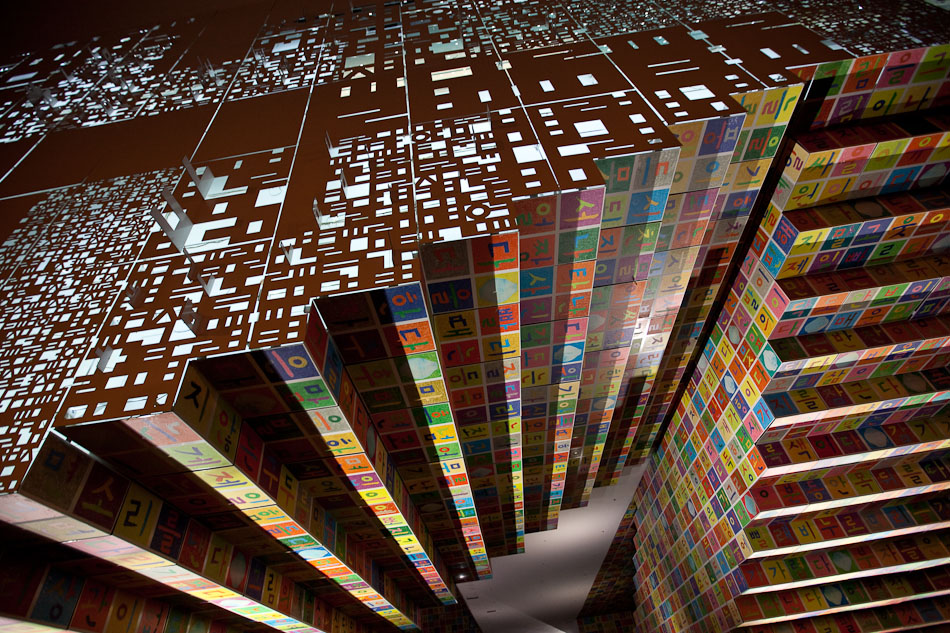

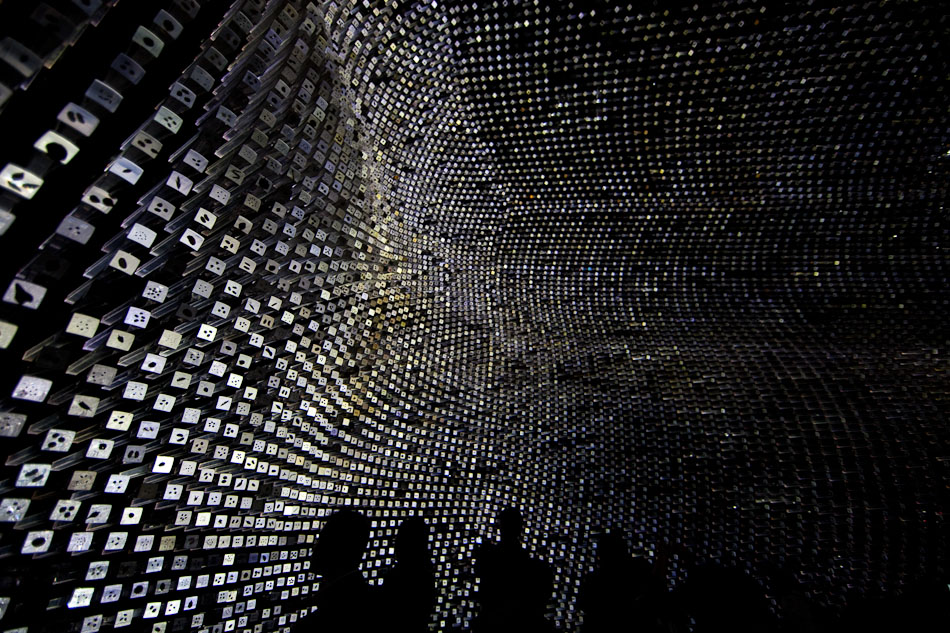

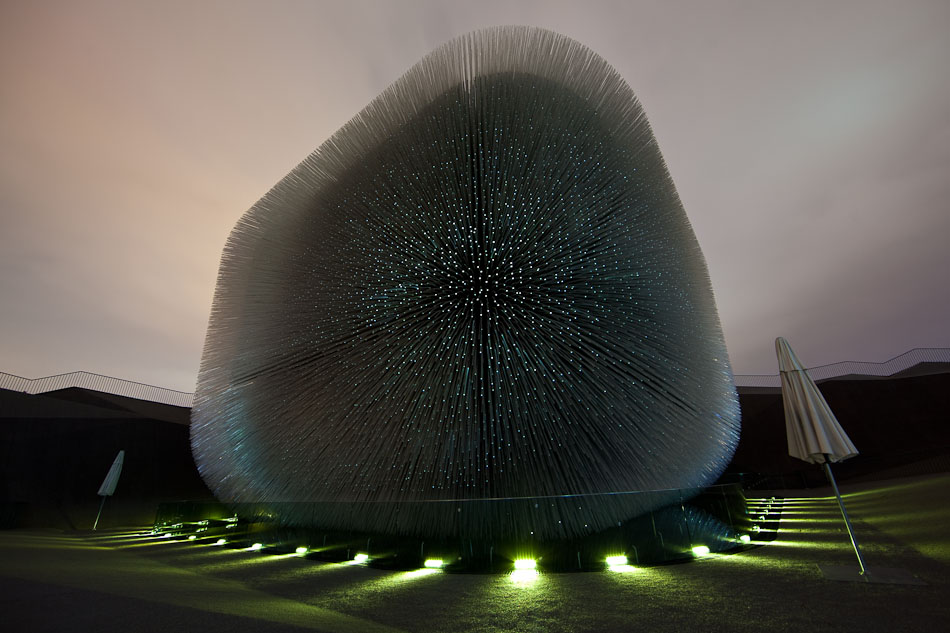

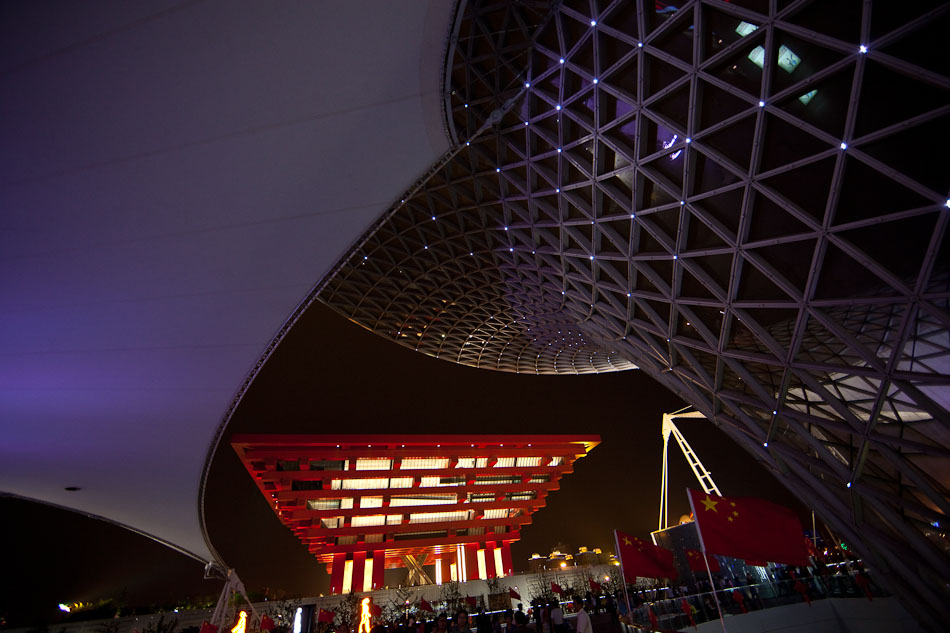

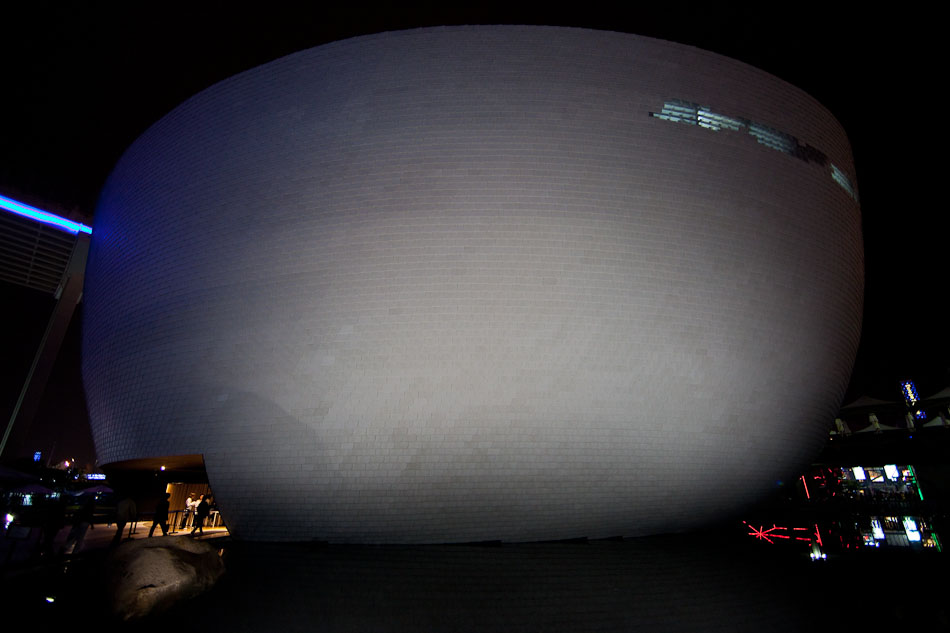

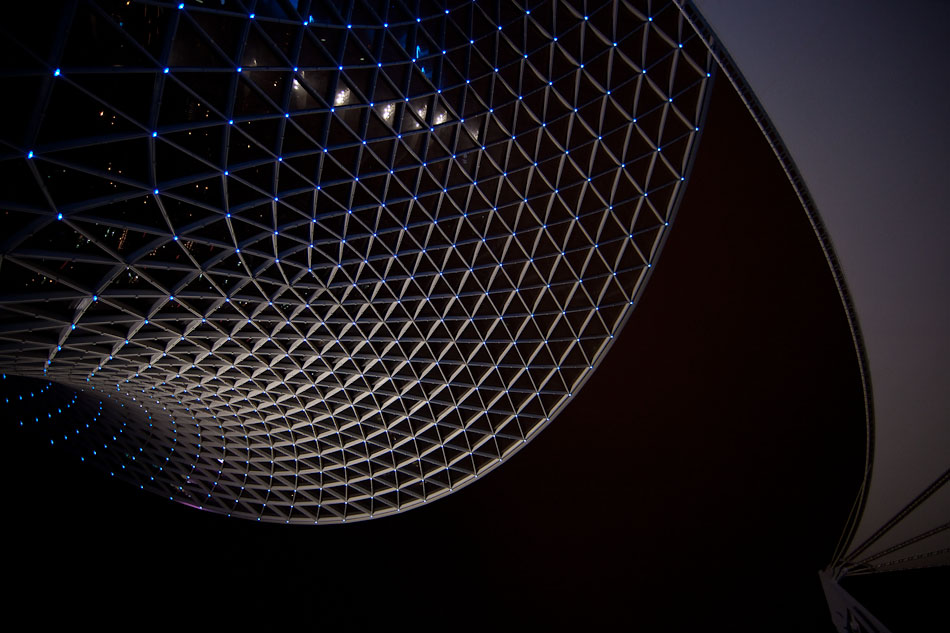

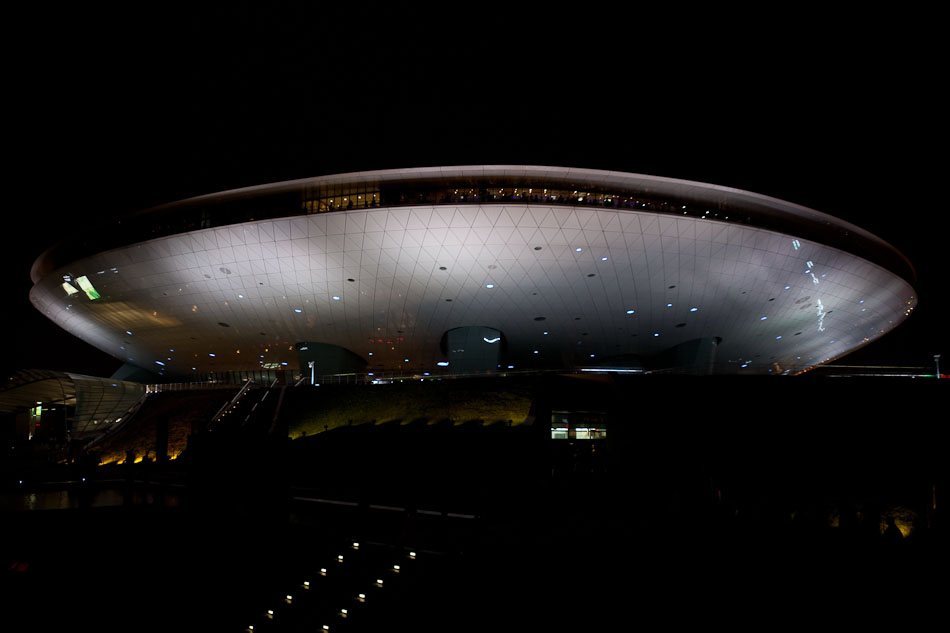

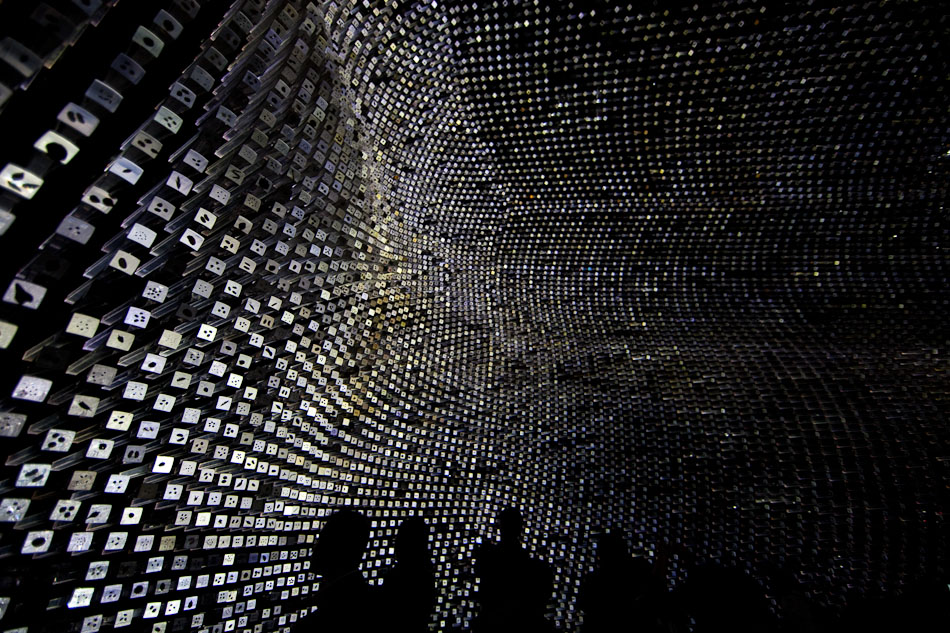

After visiting the 2010 Shanghai World Expo last week, I decided that the night time is definitely the right time to visit. During the day the crowds were overbearing and most of the pavilions less than enchanting. However, when the sun goes down, the expo turns into a festival of lights. Some of the clear architectural winners in my book were the Spanish, Korean, Nepalese and Danish with the UK Pavilion taking the gold. Designed by Thomas Heatherwick, the six-story structure is stuck like a pincushion with 60,000 willowy rods that glow and quaver in the breeze. The rods extend from the interior where at the root of each a plant seed is seamlessly inserted. The UK Pavilion is supposed to reflect the British love for gardens and emphasize the need for green space in cities. You can read more about the concept on the UK Pavilion homepage.

Sep 10, 2007 | Travel

My recent foray into Mustang represented the culmination of many desires, interests, and frustrations I bear concerning the fate of contemporary Tibetan culture and Buddhism. This preoccupation first took hold while visiting Lhasa in 2001 after living in Beijing for a year. At the time I considered the long overland journey a pilgrimage to a center of faith that held the solution to many of the afflictions plaguing consumer culture and the developing world. Although my convictions certainly evolved over the years, that first encounter still left an indelible mark on my notions of cultural transformation in communities pried open and incorporated into the strata of modern nations.

Like many travelers before me, I first sought in Tibet the fleeting aura of a Shangri-La constructed under the influence of western media, and, like many travelers after me, I became deeply disappointed with the developmental scheme imposed on Lhasa by the Chinese state. Lifeless Tiananmen-esque squares and mindless concrete buildings dominated the Potala Palace and temples scattered about the city – religious institutions functioned in a nominal fashion and only insofar as they catered to the burgeoning tourist industry and ideological whims of local Communist Party representatives. Although some certainly welcomed much change, it could not be denied that this metamorphosis was imposed on Tibetans in a brutish manner.

My hope now is not that Tibetan culture be permanently shielded so that it may return to some traditional past but that they are finally given sovereignty over major socioeconomic decisions that impact their communities and family life. Fanciful notions championing the protection and containment of an idyllic Tibet of yore have long been lost to me. More pressing needs must be addressed as younger generations of Tibetans are forced into an often-alienating process of sinocization. Tibetans are consistently denied their supposed autonomous status more so than other officially designated ethnic minorities in China.

Mustang thus represented an anomaly of great curiosity to me. Situated along the Tibetan border in Nepal, communities within this ancient kingdom shared a longstanding linguistic and religious heritage with Lhasa. Although culturally bounded to Tibet, Mustang also maintained close political ties with Katmandu and aligned itself to Nepal when the People’s Liberation Army invaded Tibet in 1951. This propitious decision saved them from the vagaries of a Chinese state that systematically destroyed religious centers and social bonds throughout greater Tibet in the ensuing years. Mustang instead became a holdout for Tibetan insurgents and fiercely guarded the sanctity of its land and ancient way of life.

It was only in 1991 when the King of Mustang permitted tourists into the region that these communities slowly opened to the outside world. Even then, visitors allowed entrance each year were capped at a thousand and forced to purchase expensive permits (regulations that persist to this day). Mustang consequently earned the moniker the “Last Forbidden Kingdom” and prided itself on nurturing a distinct and unbroken heritage. I could not help but let such preconceptions tantalize sentiments I once held about Lhasa while walking up the Kali Gandaki Valley and first spotting the deep reddish hues of Mustang’s corrugated hillsides.

In a word, the hike was spectacular. For two weeks we crossed high passes providing sweeping vistas of bucolic villages penned in by irrigated fields of pink buckwheat and golden grains. These settlements split the arid valleys in a riot of color that was only intensified by the piercingly blue skies of the Himalayas. Every bend in the trail offered new marvels and the possibility of glimpsing the massive peaks of the Annapurna region hovering amongst the dissipating monsoon clouds in the south. Then, at the end of each day, we would settle into a local lodge that usually amounted to an extra room with a few wooden beds in a family home.

Aesthetically, Mustang did not differ greatly from rural towns in Tibet that managed to avoid the dull infrastructure development implemented by the Chinese state. Except for a number of restoration projects not much had changed over the centuries. Clustered villages consisted of whitewashed adobe houses crowned with fluttering prayer flags and interlaced with gurgling channels of water diverted from the surrounding hills. Only the impressive monasteries with their ruddy walls and ornamentation broke the ubiquitous flow of architecture.

Although I was probably not the most disinterested observer, the one major difference I detected was a certain tranquility that pervaded the dimly lit rooms and cobbled courtyards of the houses in Mustang. These communities did not perpetuate the air of anxiety I constantly encountered in Tibet where an underlying current of fear still runs rampant. Mustang had largely escaped the violence and persecution suffered in Tibet over the past fifty years and did not show the lingering effects of a people uncertain of their present freedoms and future livelihood. In an incongruously dispirited manner, it came as a relief to me that even a small slice of Tibetan culture had escaped such a fate.

Communities are still bound to change in Mustang. The serenity that blanketed most of the region ruptured in many places as people expressed their impatience for roads, consistent electricity, and other important social services such as better schools and clinics. Residents do not wish to suspend themselves in a fixed bubble catering to the sentimental whims of tourists. Fortunately such decisions and the manner in which they are enacted are still in local hands. They are opening up in their own time and on their own terms – an opportunity usually not afforded to rusticated communities suddenly faced with the impositions of an outside world.

While stopping for lunch in a small village, we met a woman who had just returned from living in Queens for two years. She was cooking in the kitchen and totally indistinguishable from other residents in the valley with her native dress and manners. It therefore came as a shock when she started speaking to us in English and bantered with us about life in New York City. When asked as to why she returned to Mustang she merely gave us a small grin and simply stated, “I like living here better.” No further explanation was needed.