Feb 20, 2010 | Development, Travel

This past week I finally got to visit the developmental monstrosity that is Dubai. Nothing can really describe the audaciousness and scope of the luxury metropolis they hope to raise from the sands of the surrounding desert. Ranging from the largest mall in the world to the tallest building in the world, Dubai is building a new Babel that is already on the verge of going completely bust. For the foreseeable future however, despite the world economic downtown, the cranes are still moving as one of the largest construction sites in the world continues to lurch forward.

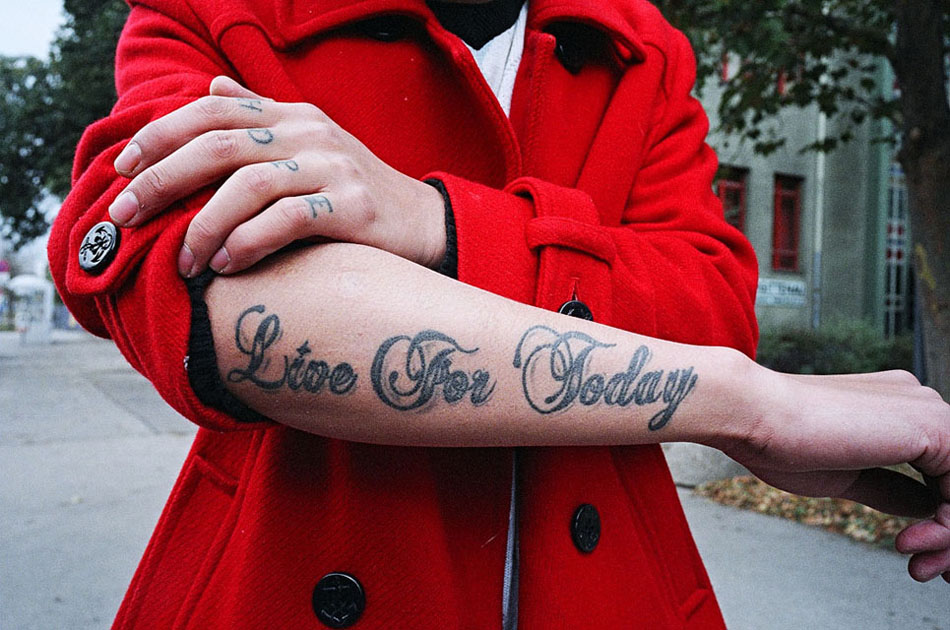

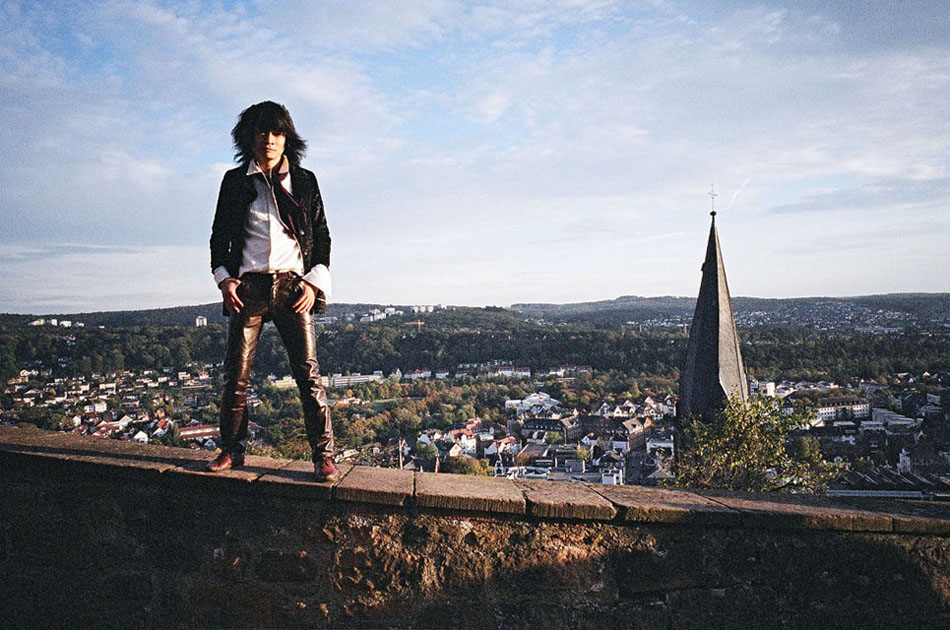

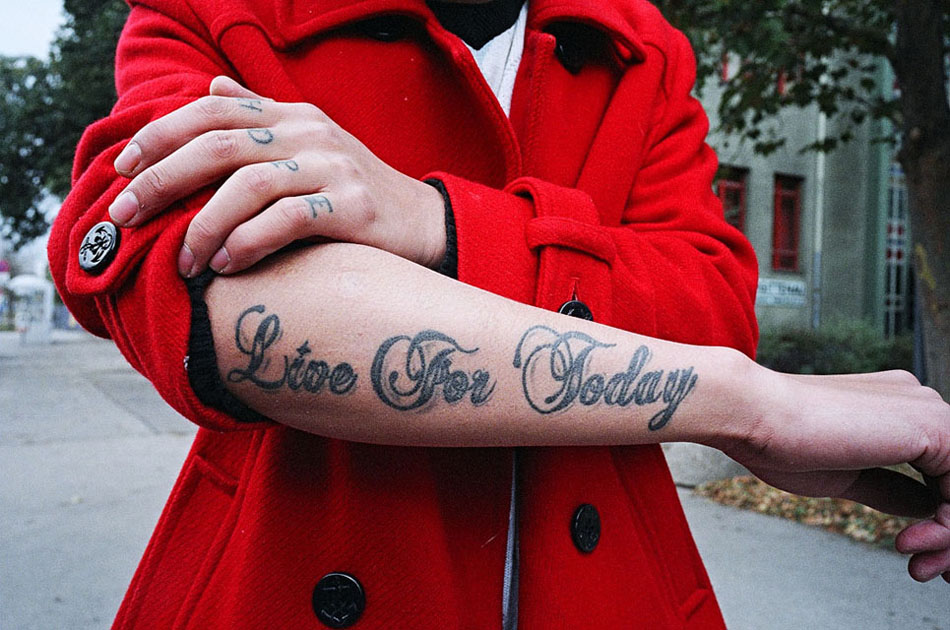

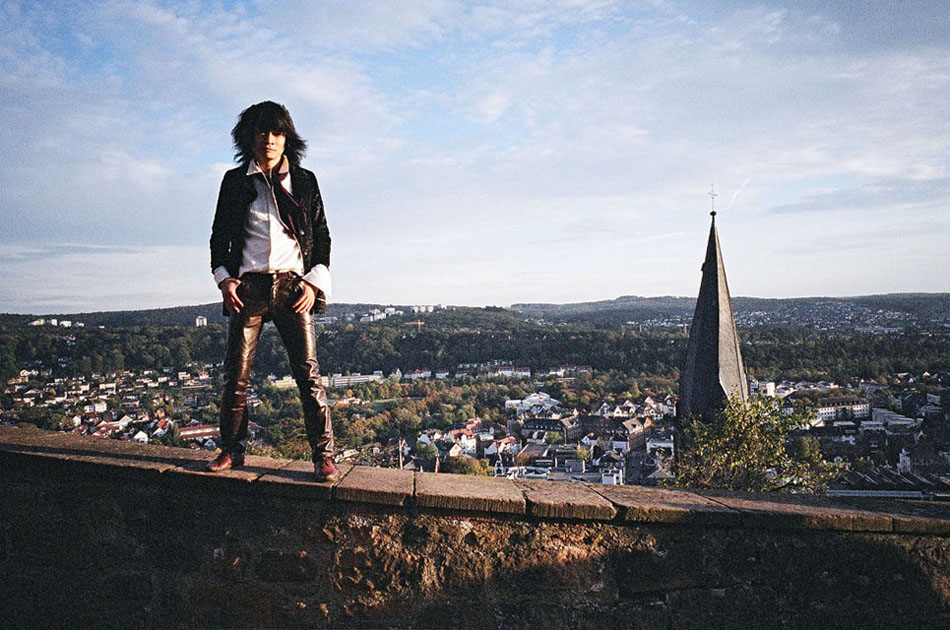

Oct 19, 2009 | Music, Travel

Joyside’s riotous, eight-year run of booze-driven concerts and five album releases came to an end in October of 2009 after a tour across Germany and Austria with Carsick Cars in support. Easily one of the most influential underground bands in China, they consistently flaunted their outright disdain for social mores and popular opinion through their bacchanalian performances and rebellious personal demeanor. High expectations were met in Berlin, Frankfurt, and Vienna and then topped with a massive concert at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. I luckily got to tag along. Although fans mourn the loss of Joyside, most are thankful that something as uninhibited and wild as Joyside lasted so long in the first place.

Nov 27, 2008 | Society, Travel

Macau’s unique character draws deeply from its eclectic cultural heritage. Both the first and last European colony in China, Portuguese sovereignty in Macau was not ceded until 1999, over 400 years after the establishment of the original settlement. Since the handover Macau has existed in a liminal realm stipulated by the “one country, two systems” policy – the Chinese state handles defense and foreign affairs but relinquishes control over domestic matters such as the police force, monetary system and political appointments. However, since Macau opened up its casino sector in 2002, the island’s socioeconomic fate was bound to the rise and fall of its entertainment resorts.

Last month I ventured to Macau to inspect the Cotai Strip, a massive development modeled after the Las Vegas Strip and home to the Las Vegas Sands’ Venetian Macau Resort. Currently the largest casino in the world, the Venetian helped Macau surpass Las Vegas in gambling revenues last year. For now Macau remains the only gambling destination within China and easily one of the most prominent within Asia. Still, the Chinese state is trying to curb the rampant profits and concomitant “dark elements” that spawn from the gambling world. Thanks to new border regulations implemented this summer, mainland Chinese can only visit Macau once every three months.

The loss of such an audience now pales in comparison to the impact of the current global financial downturn. Las Vegas Sands recently laid off 11,000 laborers and suspended work on two expansion projects planned for the Cotai Strip. MGM and Galaxy Entertainment also halted future expansion efforts. The hottest casino market in the world fizzled almost overnight. Still, a halt to the unchecked leeching of Asia’s nouveau riche might not be such a horrible turn of events. More shopping malls and roulette tables should be the least of Macau’s concerns as it continues to come to grips with its new identity as Asia’s premiere entertainment destination.

Over the past few years Macau residents have taken to the streets to protest against rampant corruption and labor issues stemming from the rise of powerful casino moguls. Now, with financial markets spiraling out of control, relying on the luxury entertainment industry no longer seems like a safe bet. For once the demand for casinos in Asia cannot meet the excessive supply in Macau. Catering to indulgent tastes at the Venetian does not fit reform-minded market trends. Even if Macau’s casinos make some sort of recovery in the coming months, the whole enterprise carries a heavier stigma of waste and decadence.

Sep 10, 2007 | Travel

My recent foray into Mustang represented the culmination of many desires, interests, and frustrations I bear concerning the fate of contemporary Tibetan culture and Buddhism. This preoccupation first took hold while visiting Lhasa in 2001 after living in Beijing for a year. At the time I considered the long overland journey a pilgrimage to a center of faith that held the solution to many of the afflictions plaguing consumer culture and the developing world. Although my convictions certainly evolved over the years, that first encounter still left an indelible mark on my notions of cultural transformation in communities pried open and incorporated into the strata of modern nations.

Like many travelers before me, I first sought in Tibet the fleeting aura of a Shangri-La constructed under the influence of western media, and, like many travelers after me, I became deeply disappointed with the developmental scheme imposed on Lhasa by the Chinese state. Lifeless Tiananmen-esque squares and mindless concrete buildings dominated the Potala Palace and temples scattered about the city – religious institutions functioned in a nominal fashion and only insofar as they catered to the burgeoning tourist industry and ideological whims of local Communist Party representatives. Although some certainly welcomed much change, it could not be denied that this metamorphosis was imposed on Tibetans in a brutish manner.

My hope now is not that Tibetan culture be permanently shielded so that it may return to some traditional past but that they are finally given sovereignty over major socioeconomic decisions that impact their communities and family life. Fanciful notions championing the protection and containment of an idyllic Tibet of yore have long been lost to me. More pressing needs must be addressed as younger generations of Tibetans are forced into an often-alienating process of sinocization. Tibetans are consistently denied their supposed autonomous status more so than other officially designated ethnic minorities in China.

Mustang thus represented an anomaly of great curiosity to me. Situated along the Tibetan border in Nepal, communities within this ancient kingdom shared a longstanding linguistic and religious heritage with Lhasa. Although culturally bounded to Tibet, Mustang also maintained close political ties with Katmandu and aligned itself to Nepal when the People’s Liberation Army invaded Tibet in 1951. This propitious decision saved them from the vagaries of a Chinese state that systematically destroyed religious centers and social bonds throughout greater Tibet in the ensuing years. Mustang instead became a holdout for Tibetan insurgents and fiercely guarded the sanctity of its land and ancient way of life.

It was only in 1991 when the King of Mustang permitted tourists into the region that these communities slowly opened to the outside world. Even then, visitors allowed entrance each year were capped at a thousand and forced to purchase expensive permits (regulations that persist to this day). Mustang consequently earned the moniker the “Last Forbidden Kingdom” and prided itself on nurturing a distinct and unbroken heritage. I could not help but let such preconceptions tantalize sentiments I once held about Lhasa while walking up the Kali Gandaki Valley and first spotting the deep reddish hues of Mustang’s corrugated hillsides.

In a word, the hike was spectacular. For two weeks we crossed high passes providing sweeping vistas of bucolic villages penned in by irrigated fields of pink buckwheat and golden grains. These settlements split the arid valleys in a riot of color that was only intensified by the piercingly blue skies of the Himalayas. Every bend in the trail offered new marvels and the possibility of glimpsing the massive peaks of the Annapurna region hovering amongst the dissipating monsoon clouds in the south. Then, at the end of each day, we would settle into a local lodge that usually amounted to an extra room with a few wooden beds in a family home.

Aesthetically, Mustang did not differ greatly from rural towns in Tibet that managed to avoid the dull infrastructure development implemented by the Chinese state. Except for a number of restoration projects not much had changed over the centuries. Clustered villages consisted of whitewashed adobe houses crowned with fluttering prayer flags and interlaced with gurgling channels of water diverted from the surrounding hills. Only the impressive monasteries with their ruddy walls and ornamentation broke the ubiquitous flow of architecture.

Although I was probably not the most disinterested observer, the one major difference I detected was a certain tranquility that pervaded the dimly lit rooms and cobbled courtyards of the houses in Mustang. These communities did not perpetuate the air of anxiety I constantly encountered in Tibet where an underlying current of fear still runs rampant. Mustang had largely escaped the violence and persecution suffered in Tibet over the past fifty years and did not show the lingering effects of a people uncertain of their present freedoms and future livelihood. In an incongruously dispirited manner, it came as a relief to me that even a small slice of Tibetan culture had escaped such a fate.

Communities are still bound to change in Mustang. The serenity that blanketed most of the region ruptured in many places as people expressed their impatience for roads, consistent electricity, and other important social services such as better schools and clinics. Residents do not wish to suspend themselves in a fixed bubble catering to the sentimental whims of tourists. Fortunately such decisions and the manner in which they are enacted are still in local hands. They are opening up in their own time and on their own terms – an opportunity usually not afforded to rusticated communities suddenly faced with the impositions of an outside world.

While stopping for lunch in a small village, we met a woman who had just returned from living in Queens for two years. She was cooking in the kitchen and totally indistinguishable from other residents in the valley with her native dress and manners. It therefore came as a shock when she started speaking to us in English and bantered with us about life in New York City. When asked as to why she returned to Mustang she merely gave us a small grin and simply stated, “I like living here better.” No further explanation was needed.

Jul 30, 2007 | Travel

Over the past year I have attentively bent my cartographic obsessions upon Central Asia. It represented a gaping hole in my world geography – a nebulous patch on the map boxed within more prominent regions. The puzzling jigsaw of borders, deserts, and inland seas nonetheless eluded any fixation in my mind. Even a month before my departure I could barely pronounce the names of areas I was to visit. I conjoined various syllables of neighboring countries and fed them to inquiring parties, “Yes, I will be visiting Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Tushkazilstan throughout August.” The amusing game made me feel better about my own ignorance, especially when people didn’t pick up on it. Newfangled post-Soviet republics convincingly sprang into existence on a nightly basis. It lent an air of mystery to the whole enterprise.

Despite such buildup the alluring bubble of Central Asia viciously popped while crossing from China into Kyrgyzstan. After struggling through initial immigration hurdles with a gaggle of rotund Uzbek ladies breathing heavily down my neck, two friends and I faced a five-kilometer stretch of hot tarmac before the first Kyrgyz outpost – a most unwelcoming no-man’s-land. Desperation soon set in after the same Uzbek ladies quickly snapped up the only empty seats in cargo trucks also waiting to clear Chinese customs and the ensuing barren expanse. All attempts to acquire spots of our own proved futile as passing drivers waved off our imploring gestures to board their vehicles. Nobody seemed interested in our plight.

Finally, after serious contemplation of crossing the inhospitable terrain on foot, a driver with a toothless grin beckoned us into his cab. We immediately crammed into the dingy compartment. Unfortunately, my initial joy upon scoring a ride blinded me to the predicament of his transport. Two trailers precariously balanced and strapped with cheap Chinese goods swung behind the ramshackle rig. The prohibitive weight of his haul limited our speed to about 5mph, thereby ruining any hope of a glorious entrance into Central Asia. Even the most stubborn mule would have easily left us behind in a wake of ruddy dust.

After an additional seven passport checks, two more hitched rides, and an officious interrogation regarding the intentions of my stay in Kyrgyzstan, I was finally in Central Asia. That fleeting moment of exultation was soon followed by more despair however. Border towns do not always lend the best impressions of a country, and the massive junkyard that comprised the frontier village offered no signs of enticement for the month of travel that lay ahead. Luckily an enterprising young girl selling meat pies took the edge of the whole escapade. Dusty and downtrodden, I nibbled on the tasty treat and peered about for a car to take our group to Osh.

Three hours later I was passing in and out of consciousness in the back of a small Russian jeep – every bump and rut on the haphazard road unfailingly slammed my head into the passenger window. My restless slumber finally came to an end when our driver stopped to assist another vehicle suffering massive engine failure. I stumbled out of the car only to be met with a vision more bizarre than the dream-fueled haze fading from my sensibility. A pastoral spread of yurts, farm animals, frolicking youth, and glossy Soviet trailers backdropped by the mighty Pamir Alay range spread out before us.

The proprietors of the peculiar estancia immediately offered us teeming bowls of yogurt and ushered us behind a trailer where we sat observing a young woman intently weaving thick bands of rope used to bind the slender frames of their yurts. The deft movement of her hands captivated me until a contumacious young burro disturbed my meditation, forcing me to chase him around the yard a few times. I had to cut my caper short though when the Uzbek ladies who so brusquely purloined our rides at the border that morning pulled up in their own jeep to rest and investigate the scene. I prepared myself for a mortal showdown.

Standing in the front yard with my bowl of yogurt and a clenched fist, I put on my most imposing visage. Like any hardened Asiatic traveler, I held longstanding grudges for anyone who broke queues and these particular offenders snagged our rides across the border without a hint of remorse. The Uzbek ladies, bedecked in gaudy robes and sporting flashy gold crowns on their teeth, took no notice of me however and quickly entered the trailer for a mid-morning snack. Noting their apparent disinterest, I continued my own exploration of the nearby area while our driver continued to slam the engine block of his friend’s car with a large mallet.

After playing with the rest of the farm animals including a gregarious brood of chicks that would expectantly clamor about your feet in search of food, loud accordion music started blasting from the front yard of the homely trailer. The Uzbek ladies had thrown open the doors of their jeep and instigated a dance party using a surprisingly loud stereo system. In spite of earlier resolutions, my ill will began to melt as the energetic pack of bodies bounced about the yard, wrists twisting into various exotic poses at every beat. They soon engendered a raucous wresting match amongst the children living in the yurt and attracted the expectant attention of neighbors on the surrounding hills. I could no longer harbor any discontent in the face of such impromptu revelry. Even lazy dogs enjoying afternoon naps emerged from their shady corners to bask in the energy of the boisterous crowd.

Thus, bowl of yogurt firmly in hand, my love affair with Central Asia firmly took root. The sentiment could not be resisted. I surrendered to the upbeat accordion music sweeping across the high plateau and threw my lot in with the spontaneous frivolities taking place around me. Such absurdities must always be embraced and I was in no position to refuse such a gift.

Jul 16, 2007 | Travel

After the resplendent Tashilhunpo and Sakya monasteries, the road west from Lhasa soon enters one of the most remote regions in the world. Outside the infrequent villages only herders seeking high summer pastures inhabit the wide valleys spotted with electric-blue lakes. These desolate stretches of earth girdled by impenetrable snowcapped mountains engender a sublime trepidation, as if one has trespassed upon an inhuman landscape fit only for the gods and demons that adorn the walls of local temples. Here heaven touches the earth and yields Tibet its undisputed title as the roof of the world.

Western Tibet, known as Ngari, also remains a land of pilgrimages, chief among them Mount Kailash. For Hindus Mount Kailash is the domain of Shiva, Lord of the Cosmic Dance – both destroyer and creator. For Tibetan Buddhists Mount Kailash is the domain of Demchok, a wrathful manifestation of Sakyamuni – the historical Buddha who set the Dharma Wheel in motion some 2,500 years ago. For all faiths that venerate Mount Kailash the pilgrimage culminates in a ritual circumambulation of the mountain. Hardy locals complete the 32-mile circuit in a single day. Such a physical feat was not on my agenda however, especially with an extra thirty pounds of camera equipment strapped to my back.

I opted for a three-day trekking plan in order to stay at the monasteries en route and enjoy the views of Mount Kailash’s magnificent faces. Even with the extra time the trek was no small feat – the trail’s altitude averaged at about 15,000 feet and crossed a pass over 18,000 feet on the second day. These heights compounded by the occasional hailstorm added to the surreal surroundings. Luckily the rarefied atmosphere only amplified my lightheaded musings. Sore thighs and shortness of breath were quickly forgotten as I snacked at the summit of the pass with a group of other pilgrims looking to wipe away a lifetime of sins through their pilgrimage to the sacred mountain.

The descent proved more formidable. My legs turned into jelly near the bottom of the pass, making a long break at one of the many dark nomadic tents doling out tea and noodles necessary. Here I relaxed with a group of young Tibetan men dressed to the nines for the important pilgrimage – heavy woolen coats were complemented by polished leather cowboy hats and colored sunglasses that even Bono would be embarrassed to wear in public. Their modish attire clashed amidst the older pilgrims who unwaveringly twirled prayer wheels while whispering mantras to the deities dwelling atop the surrounding peaks.

The dark corrugated faces of elderly Tibetans exhibited decades of weathering at the hands of bitter winters and a piercing sun. Despite the Chinese state’s attempts to raise the quality of life for scattered provincial populations, a large majority of Ngari still relied on herding and sustenance farming for survival. The Tibetan plateau’s harsh environment forgave little in their lifetimes and the long pilgrimage to Mount Kailash represented for some the ultimate appeal for release. The past decade has been an especially incongruous time for them though. The specter of imposed socioeconomic reforms and their entailing skewed notions of progress loomed ever large on the horizon.

Ngari encompasses a major swath of bleak tundra that persists relatively untouched by the commercial markets spreading from Lhasa. Still, like Kham in the east, newly built roads are slowly opening insular communities. Increasing numbers of trucks and tourists ply these once isolated routes and bring with them an all too familiar stream of consumer goods and ploys. I can only hope that the decisions as to what manner and extent these areas open up to the outside world remain in indigenous hands – a liberty not often granted to these supposedly autonomous regions.