MEGABLOCKS

MEGABLOCKS

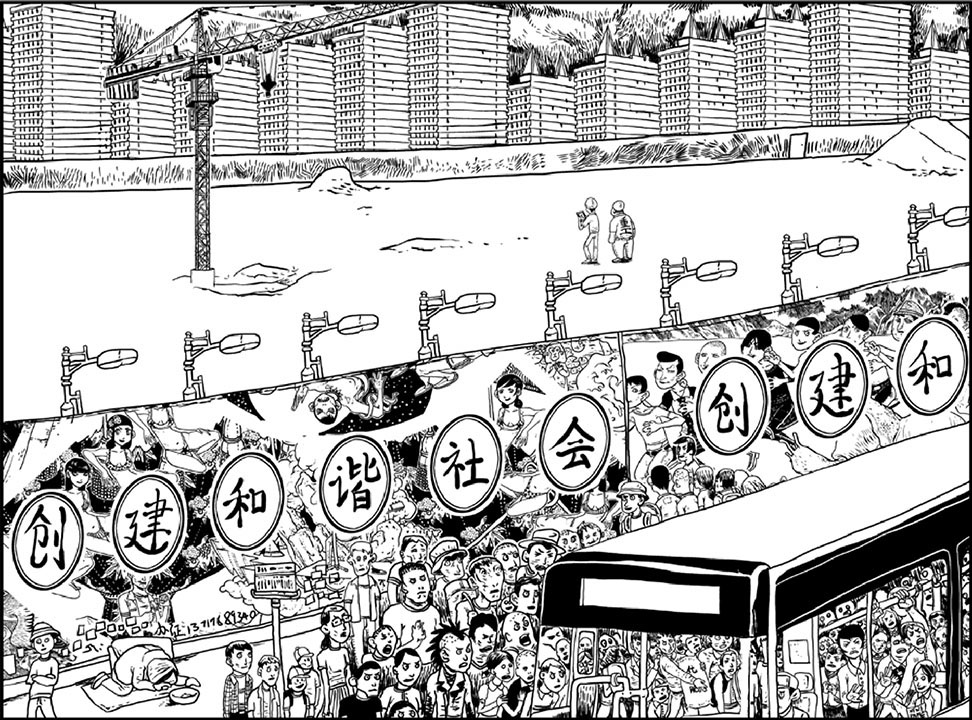

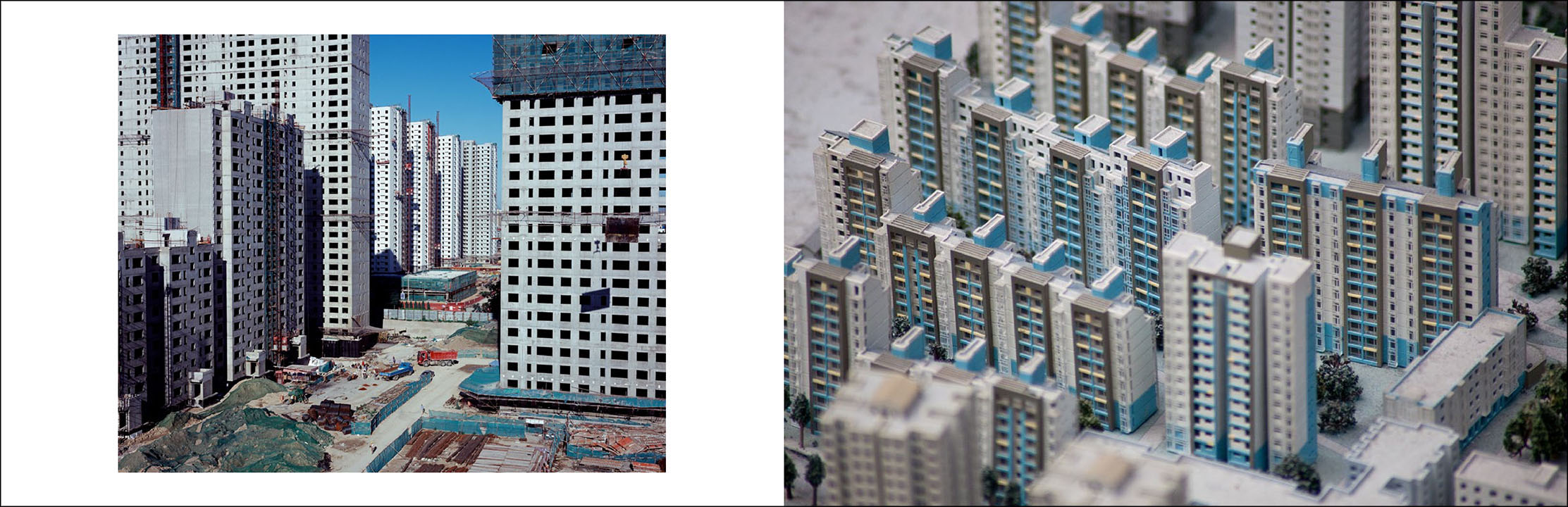

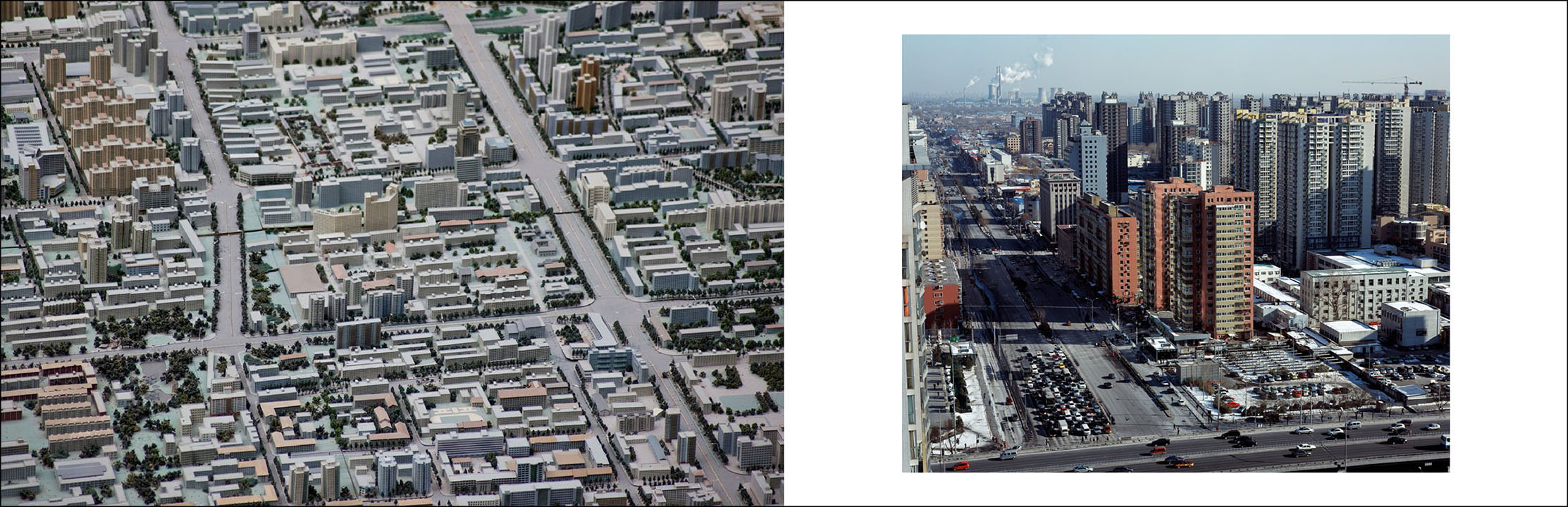

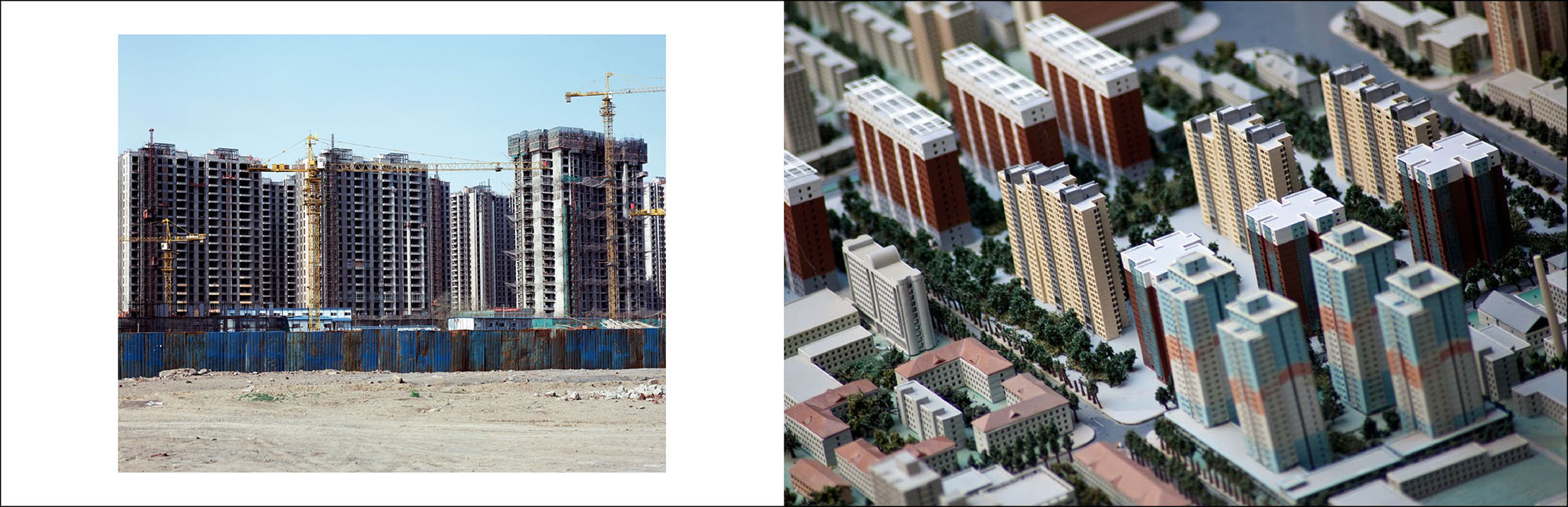

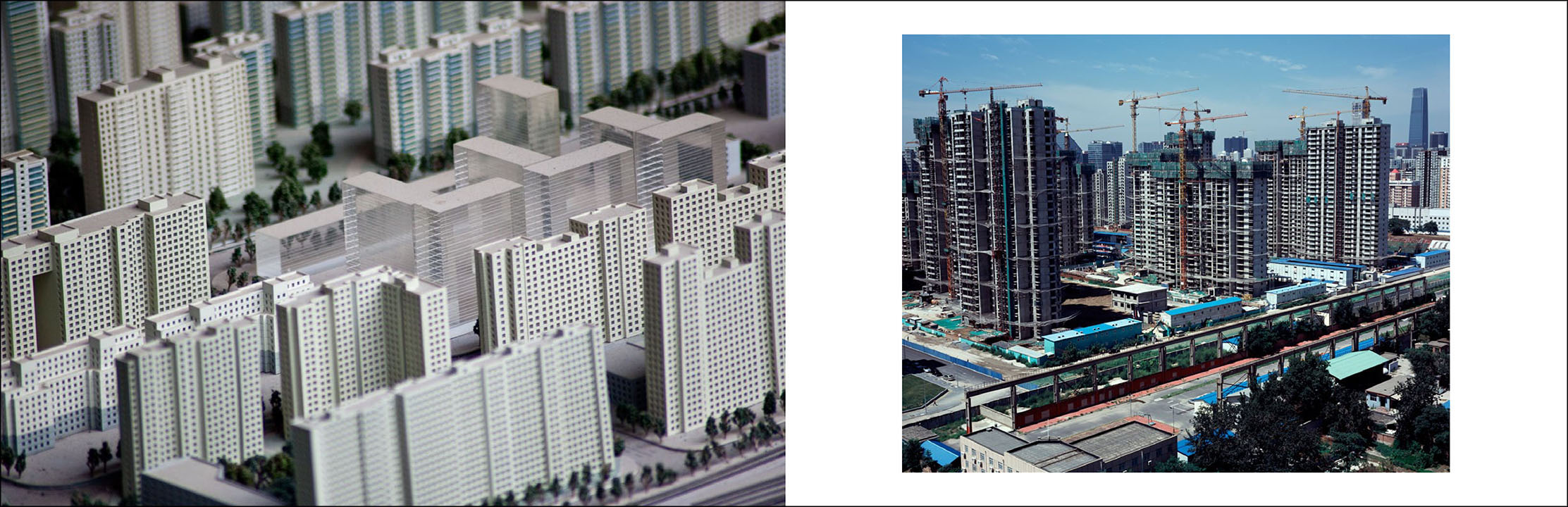

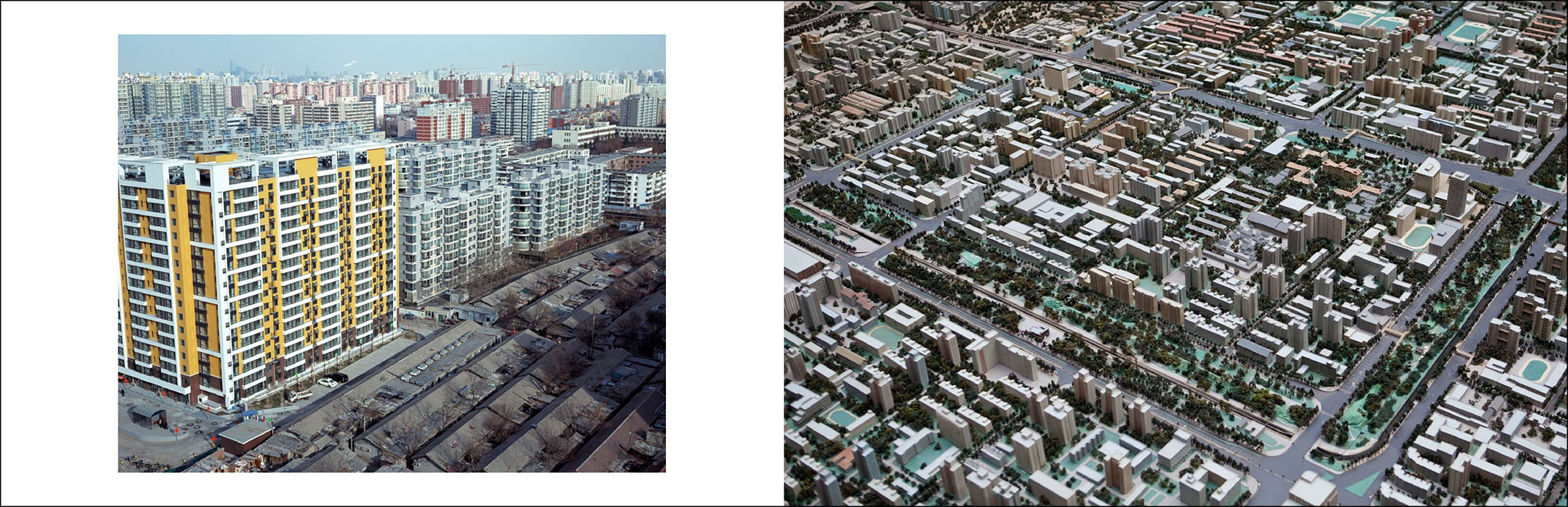

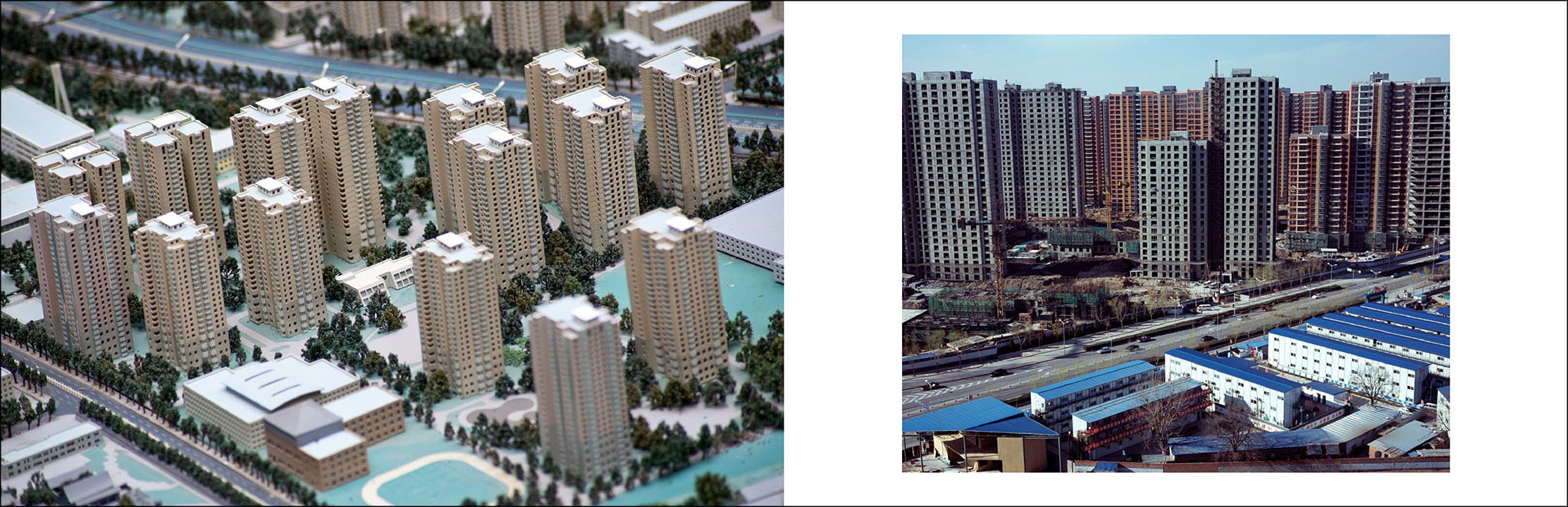

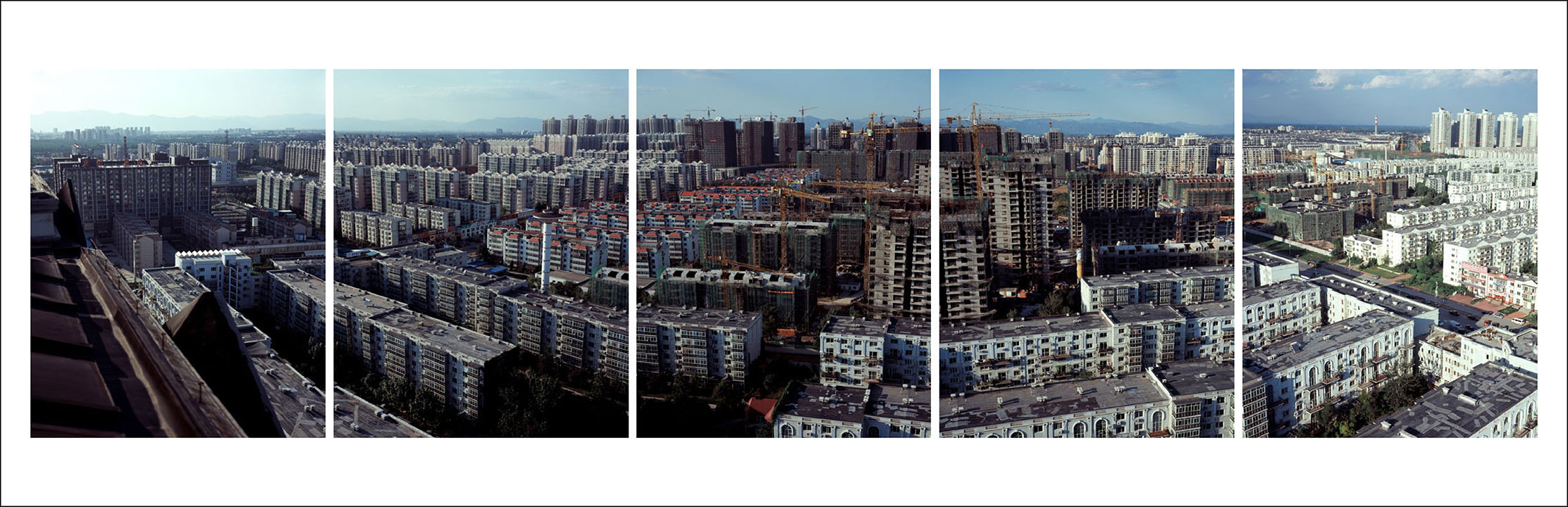

China was once dubbed the “Sick Man of Asia” when it failed to resist the impositions of colonial enterprises after the Opium Wars. Now such a title seems laughable. The sheer immensity of China’s infrastructure development far surpasses any human enterprise ever mounted. An additional 350 million people are expected to move into cities across China by 2025 with the overall urban population set to exceed a billion by 2030. In the not too distant future, there will be more than 200 cities sporting populations over a million in China: imagine ten New York cities worth of skyscrapers erected in just fifteen years. The purchasing power of these newly minted city dwellers will also rival those in developed countries. There is little doubt that China is bound to be the largest and most lucrative consumer market on the planet. The dawn of China’s Gilded Age is already upon us, and it is impossible to ignore the lifestyle choices of the nouveau riche who drive it. This unprecedented transformation is already taking shape in a number of cities across China including Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Shenzhen, and Tianjin. Smaller municipal governments look to these metropolises as archetypes of urban development. As the host of the Summer Olympic Games in 2008 and the seat of the central government, Beijing in particular is held aloft as a model to be emulated. The photography essays and illustrative elements in this book thus examine the formation of a new Beijing, one that supposedly reflects the oft employed political lingo that demand “modern” and “civilized” cities that encourage “harmonious” living. The manner in which urban planning and infrastructure development is actually manifesting, however, does not always reflect such optimistic rhetoric. Recently developed areas of Beijing surrounding its former imperial core are dominated by megablocks, where huge swaths of land are handed over to developers to be fashioned into towering apartment high-rises interwoven with malls and public spaces. Once built, they form distinct urban islands, bounded by grand avenues and further hemmed in by the large highways that encircle Beijing. Entire districts are laid out and rebuilt in such a fashion – like cogs in a machine switched out for newer parts. This contemporary breed of megablocks destroy any sense of fluidity in greater Beijing. The imposing and often monotonous facades of these megablocks belie an elaborate transformation of social practices that occurs at an alarming pace across the city. Through a mix of photographs from a detailed diorama of Beijing located in the official Beijing Urban Planning Exhibition Hall and actual urban landscapes both built or under construction, the following section introduces how megablocks are physically imposing new frameworks for standards of living and consumption for the rest of China. This is the gap between the clean and hopeful vision of a harmonious Beijing found in sanctioned models and how it is actually being shaped on the ground.

HOMES

HOMES

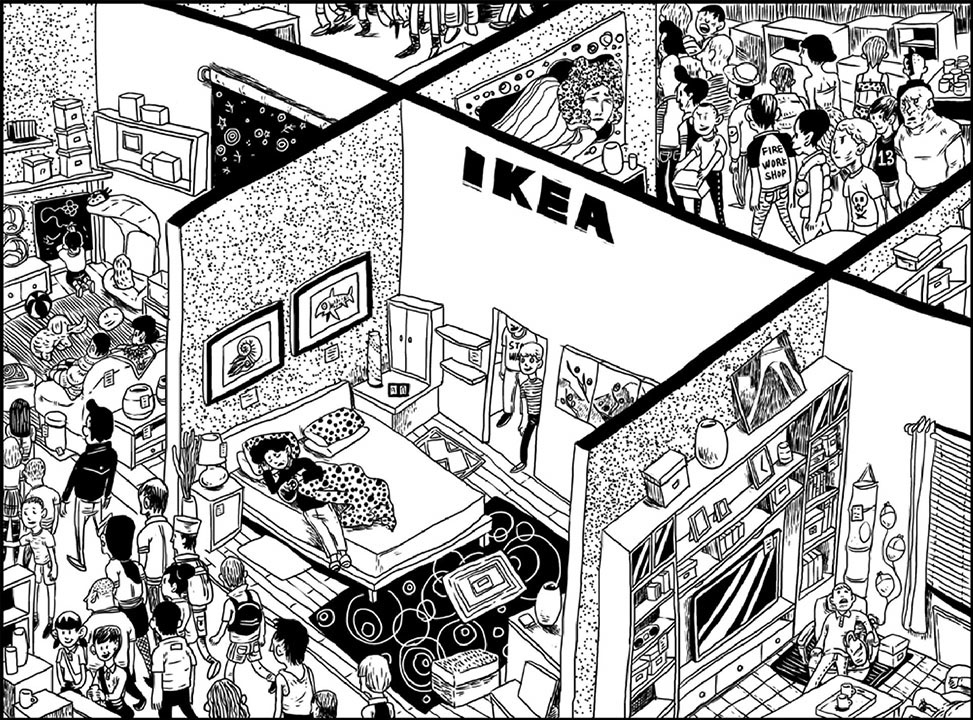

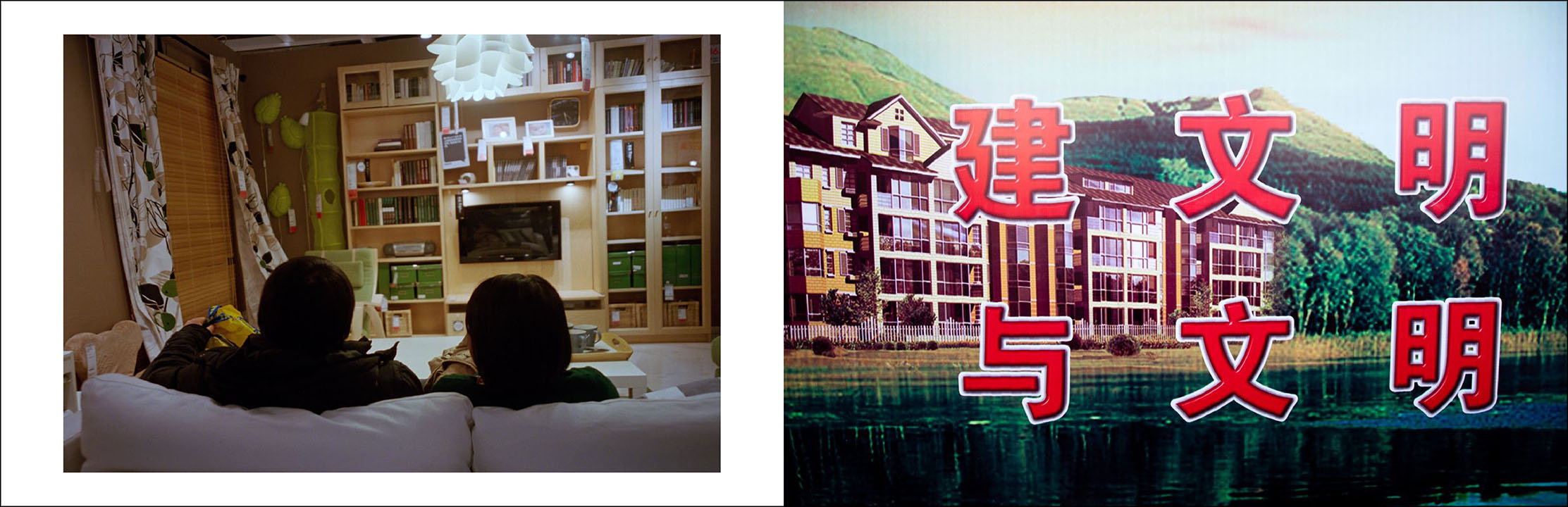

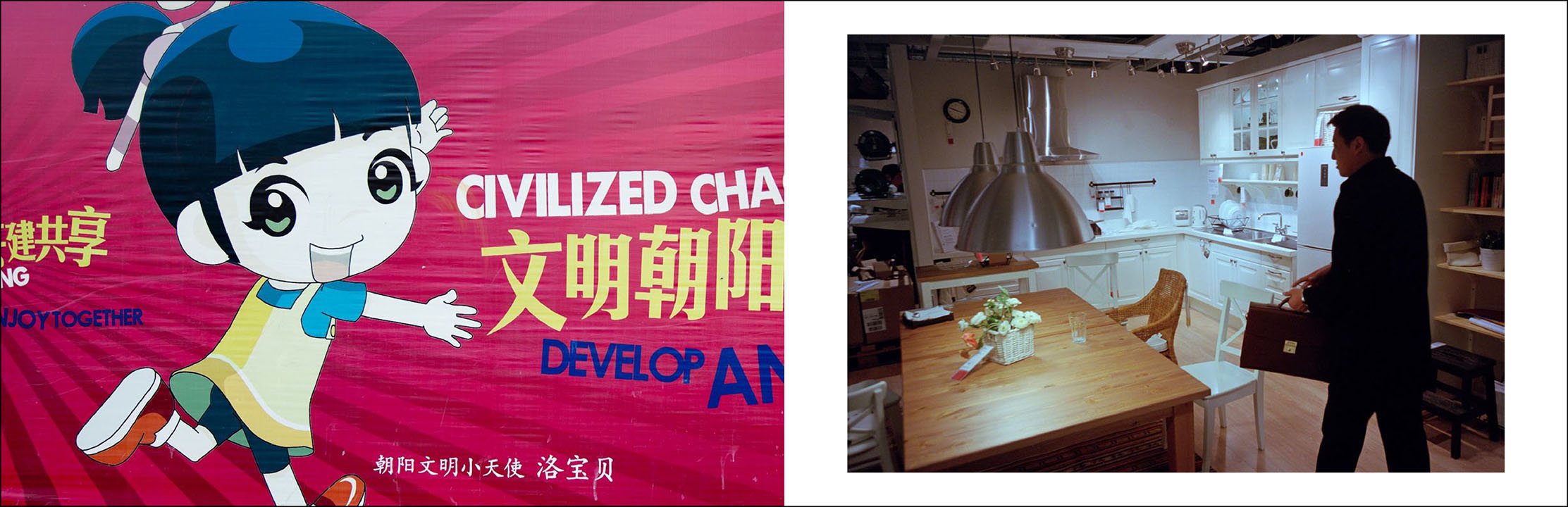

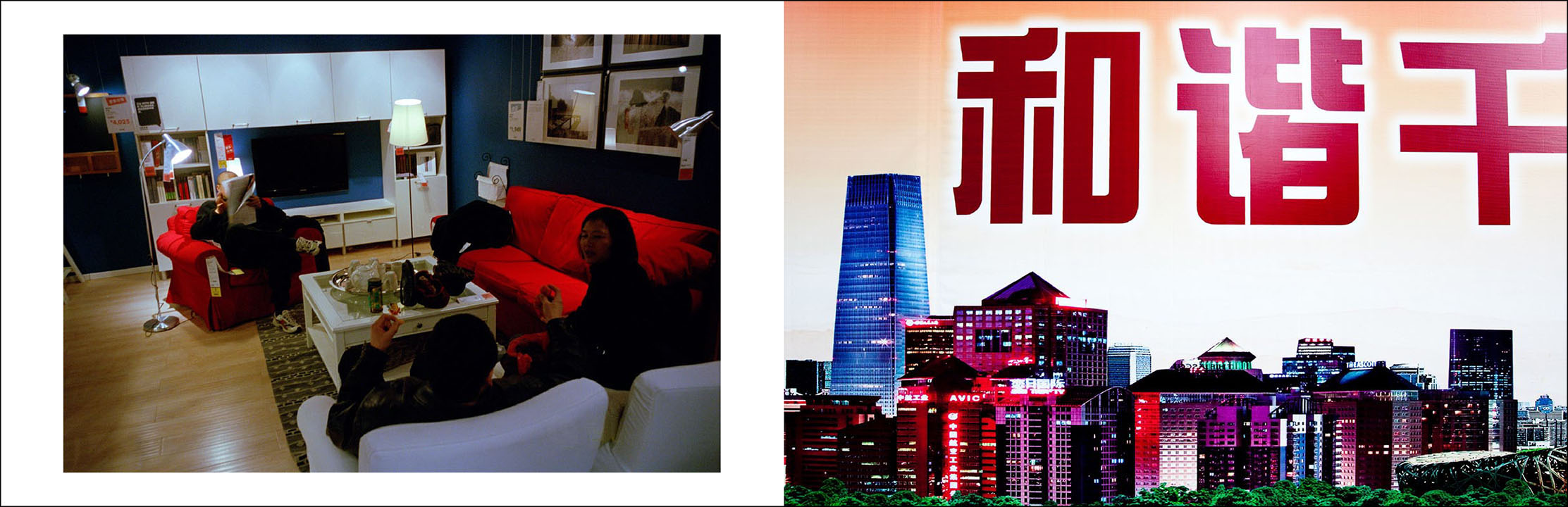

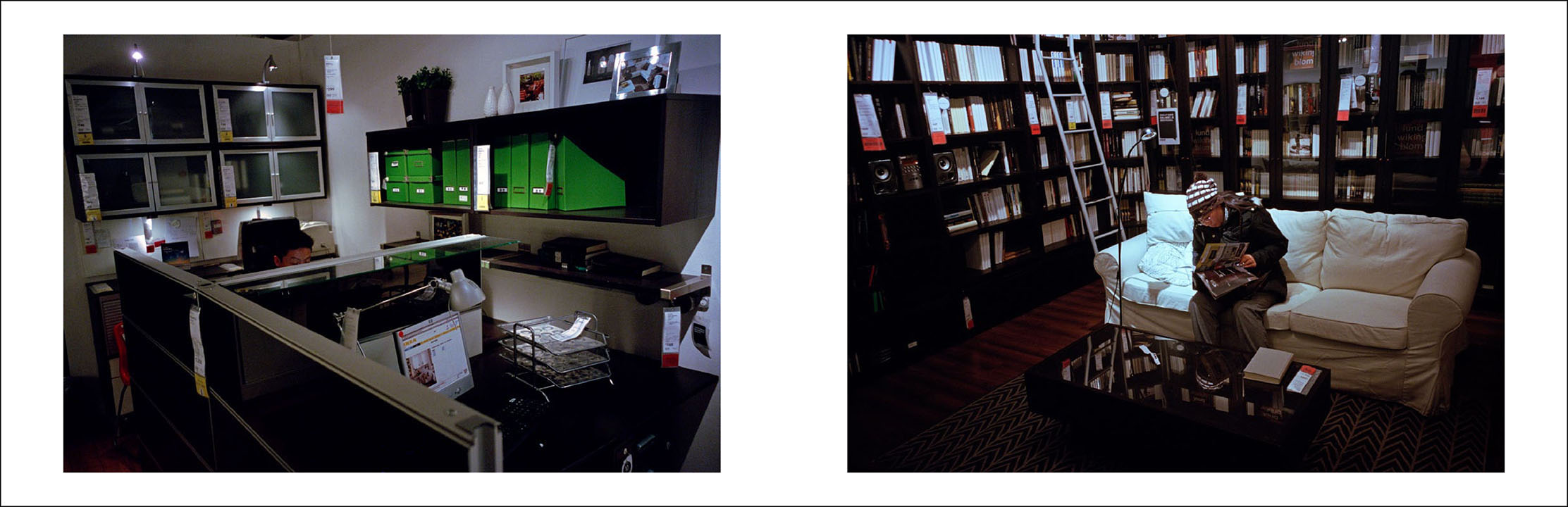

As megablocks become the norm across Beijing, they not only drastically reshape the city but also the manner in which people live and consume. These next three sections look at a different space: one in which consumer desire is provoked through imaginative interaction with products and services. In the 1970s the three most valuable assets a leigh family could own were a watch, a bicycle, and a sewing machine. These are known as the “old three” as they were replaced in the 1980s by the the “new three” which included a television, a refrigerator, and a washing machine. Now the pinnacle of material assets and indicators of social status are a home, a car, and travel. The greatest chunk of Chinese disposable income is spent on these and are a must for Beijing’s nouveau riche. Out of these, the megablock’s greatest impact has been felt in the home. Gone are the courtyards and small alleys of old Beijing where people largely lived on the streets and interacted in close-knit communities. Megablocks now encourage social atomization in their individual, western-style apartments. Unlike early Communist-era apartment blocks where families cooked in communal kitchens and even in the hallway, the new megablocks provide indoor kitchens. One might go for years without ever meeting or knowing a neighbor. Global commerce quickly took notice. With China’s burgeoning consumer market in its sights, Ikea opened in Beijing what was at the time its single largest outlet in the world. Stimulated by the construction boom of megablocks and the increasingly materialistic nature of nouveau riche, the capital proved fertile ground for its economical but trendy furnishings. Ikea’s 42,000 square meter flagship store is now a magnet for Chinese consumers. Shoppers pack the isles to peruse a seemingly endless parade of products and the especially popular showrooms. The faux kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices are wildly alluring amongst patrons who sometimes visit just to spend a leisurely afternoon lounging on the plush furniture with no real intention of making a purchase. Desirous looks and gestures abound as they enact little domestic dramas while settling into couches, armchairs, and beds. Although catering to nonpaying customers may appear like wasted effort, Ikea tolerates their presence. Even though they might not buy anything now, they will in the future. Ikea looks forward to satisfying their nascent materialistic urges spawned by newfound nesting habits. Each photograph is thus framed to suspend the customers in their appropriated Ikea environments, as if they were in their own homes. The patrons easily overlook these details as the novel surroundings goad and shape their notions of what constitutes a residence. The other photographs are taken of government propaganda billboards found on the exteriors of megablock construction sites around Beijing. They reflect the ambiguous “modern” and “civilized” rallying calls that are so closely associated with lifestyles sold at Ikea.

CARS

CARS

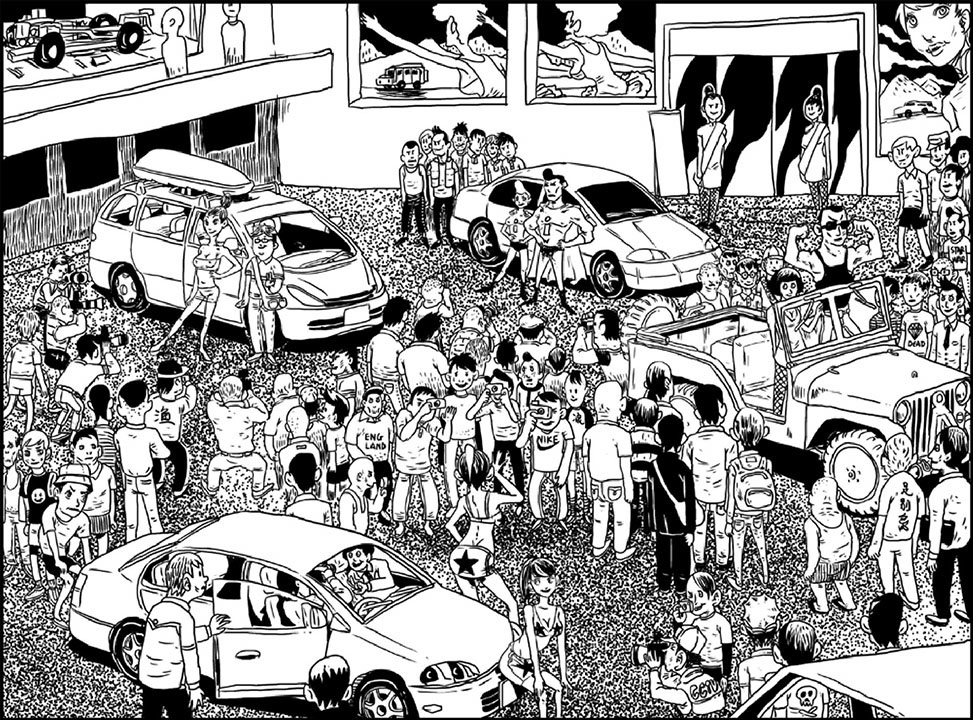

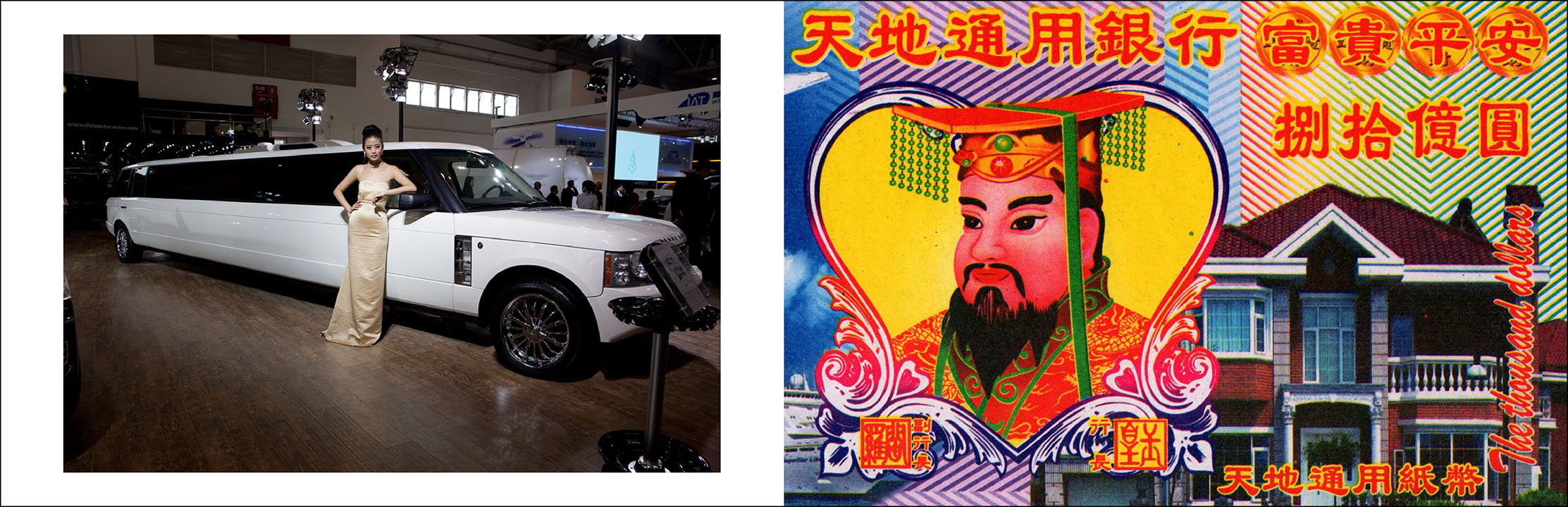

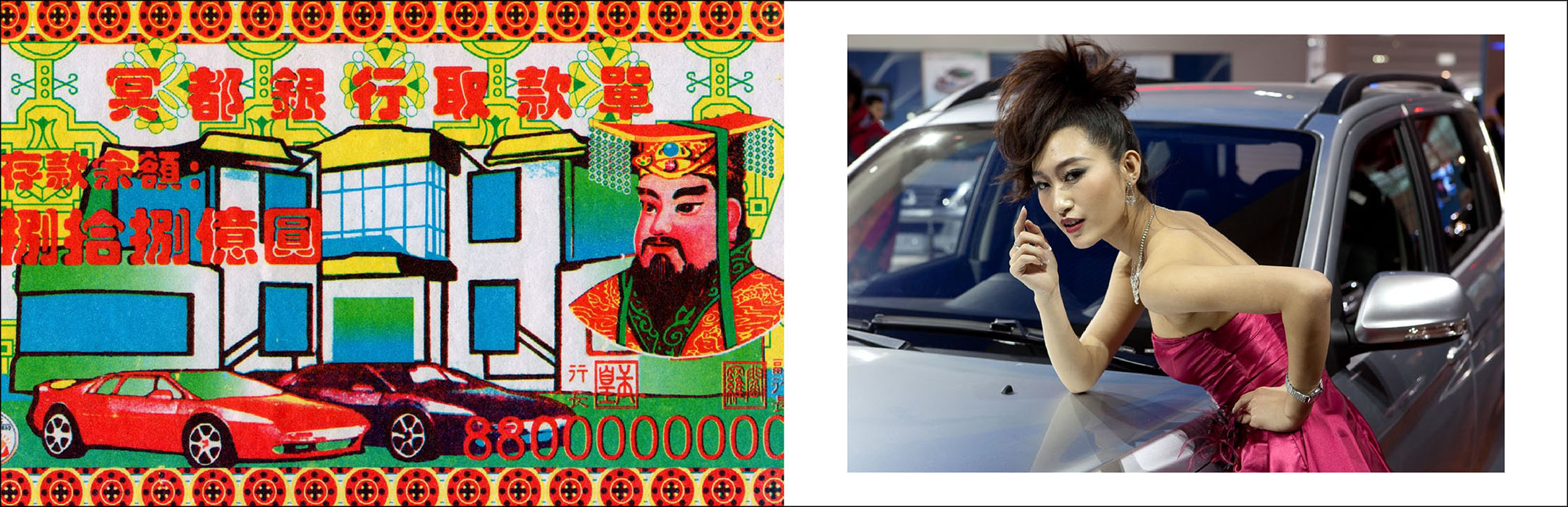

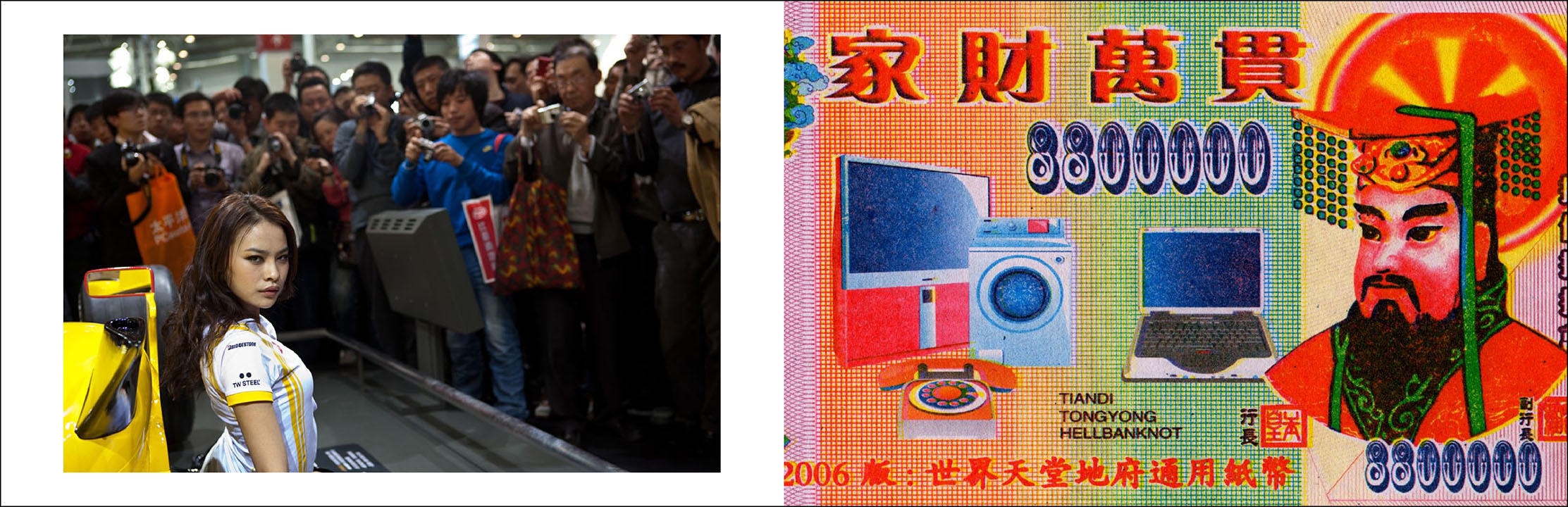

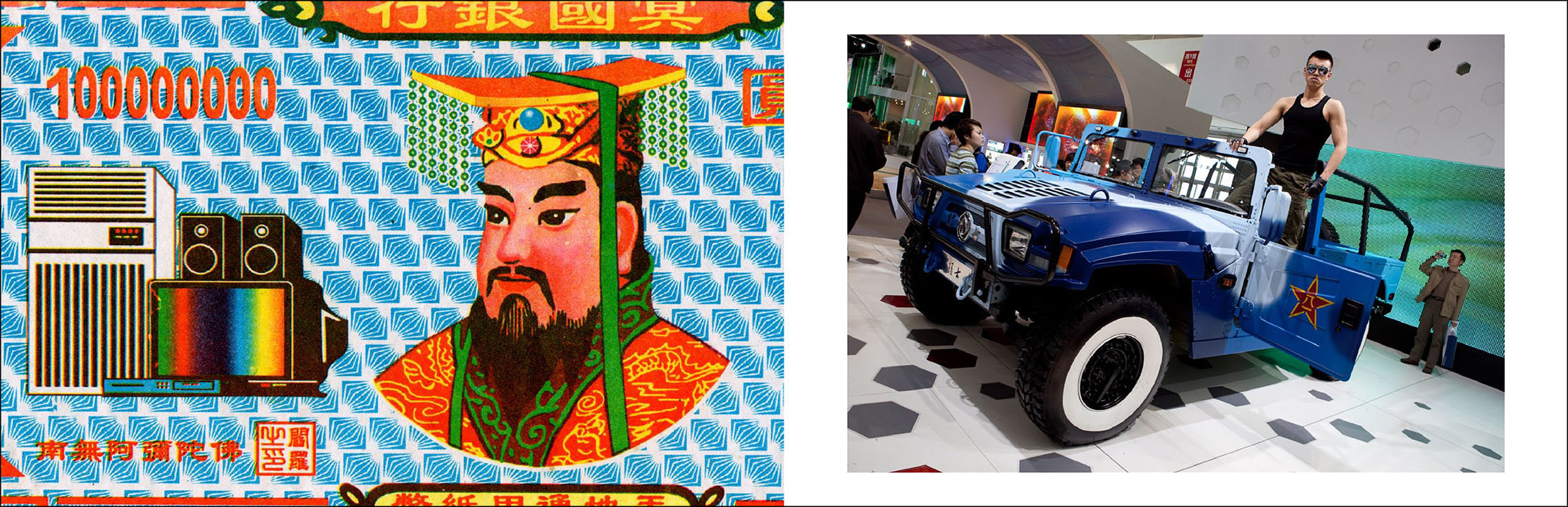

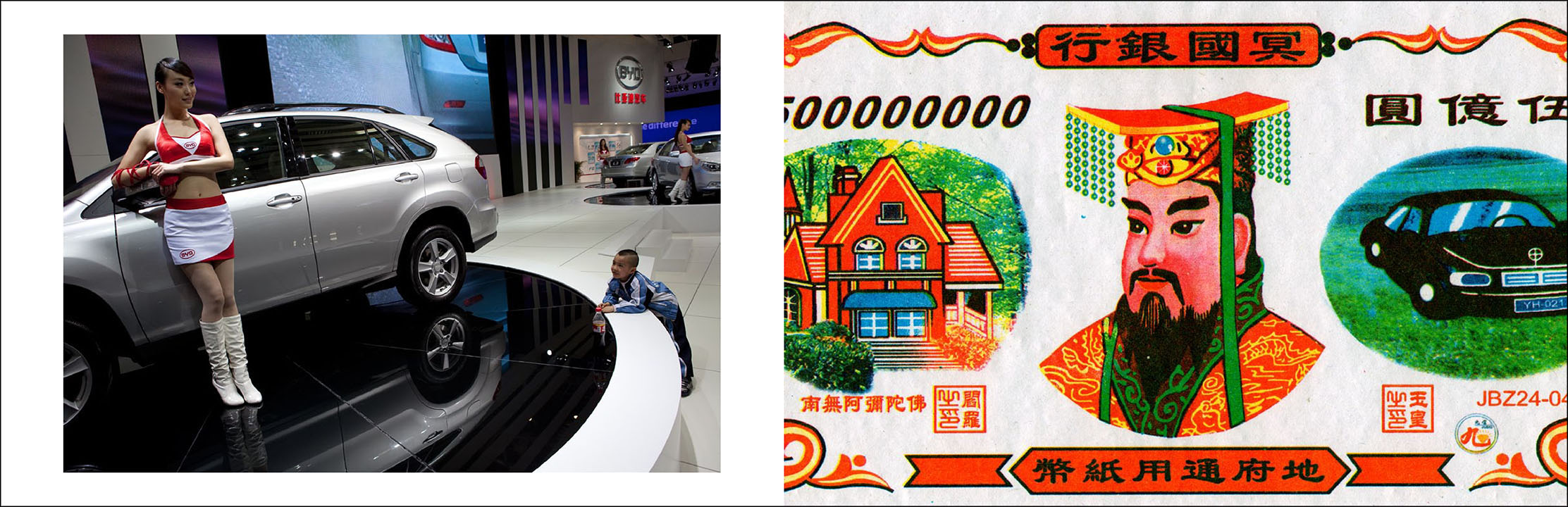

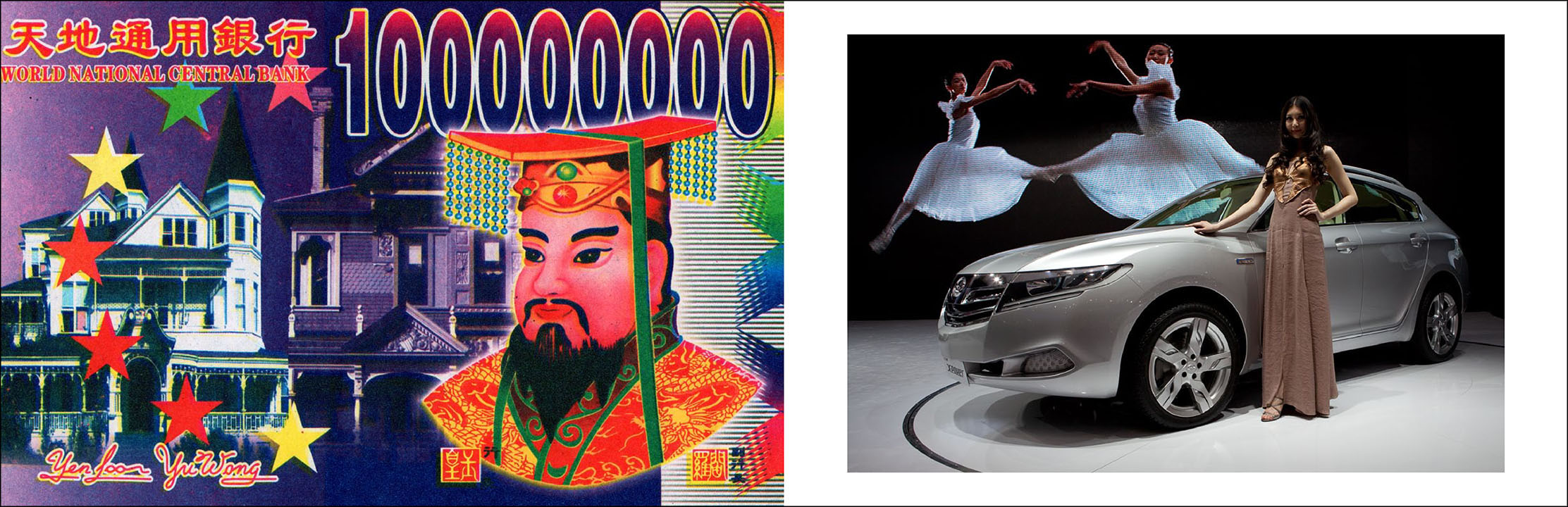

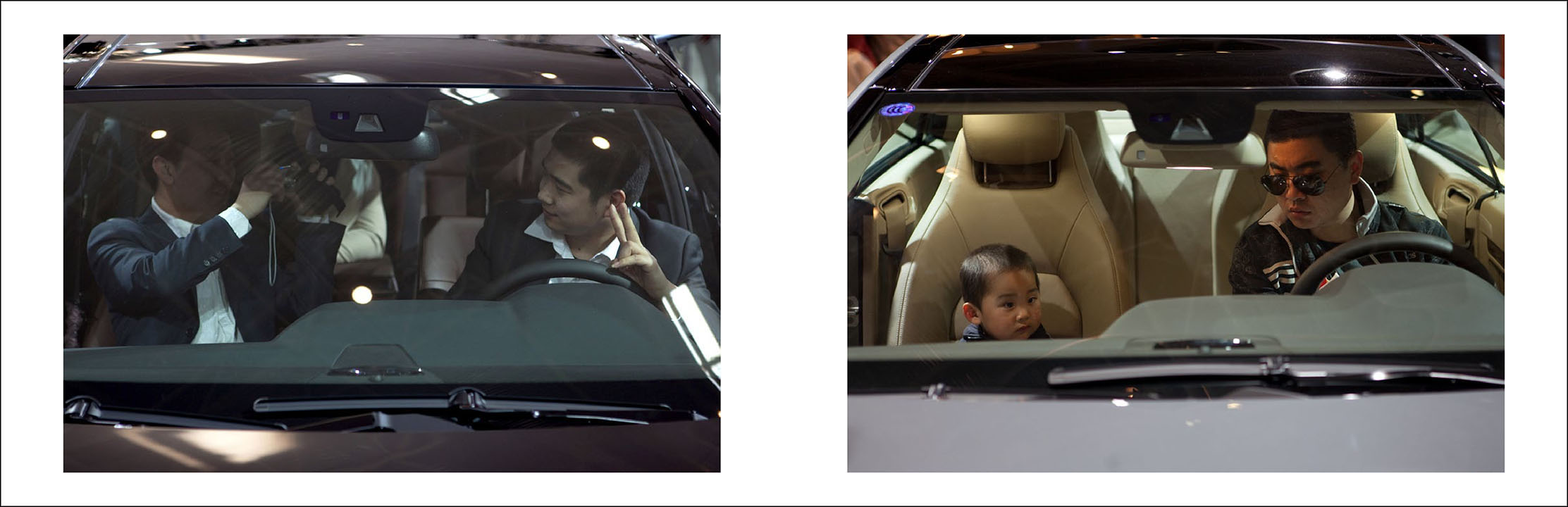

The impact of megablocks on Beijing moves far beyond the home. They also fuel a reliance on cars to move around the city. Urban planning that caters to megablocks is not pedestrian friendly. Obstructed by massive highways, the only way to get around on foot is via out-of-the-way sky bridges and underground walkways. Although Beijing is working on expanding public transportation systems, many remain overcrowded and do not effectively cover the entire city. Outside of pure necessity, Beijing inhabitants also have a newfound love affair with the car itself. It is easily one of the most potent and hyper-sexualized commodities in the country. Vehicle purchases in China already surged 45% in 2009, surpassing the United States with 13.6 million vehicles sold, and the escalation shows no sign of stopping. In the first half of 2010 more than 1900 cars were sold per day in Beijing alone. Beijing is already facing crippling traffic jams on a daily basis with 4.5 million cars in action. On top of this, projections indicate that there will be 7 million cars on Beijing’s streets by 2015. All the stop-and-go traffic has led to a maxim among taxi drivers that highways resemble parking lots more than thoroughfares. Starting in 2011, the municipal government was forced to implement regulations limiting the distribution of new license plates in the city. The greatest manifestation of this car craze is the biennial Beijing International Automotive Fair where major manufactures around the world come to pay homage to the fastest growing car market on the planet. With scantily clad models striking poses in every booth, thousands of Chinese car enthusiasts clamor to take a seat in their favorite vehicle in giant exhibition halls. Much like patrons of Ikea in the faux showrooms, attendees imagine themselves in the cars and make friends photograph them in their favorite vehicles. Alongside shots from the Beijing International Automotive Fair are hell bank notes that Chinese ritually burn every year to give offerings to their ancestors. The objects on the currency when burnt are supposed to be received by their ancestors and propitiate them. Much of the currency is now decorated with cars, homes, appliances, cruise ships, and other luxuries – supplanted by objects of newfound consumer desires. People not only need a car now, but also in the afterlife.

VACATIONS

VACATIONS

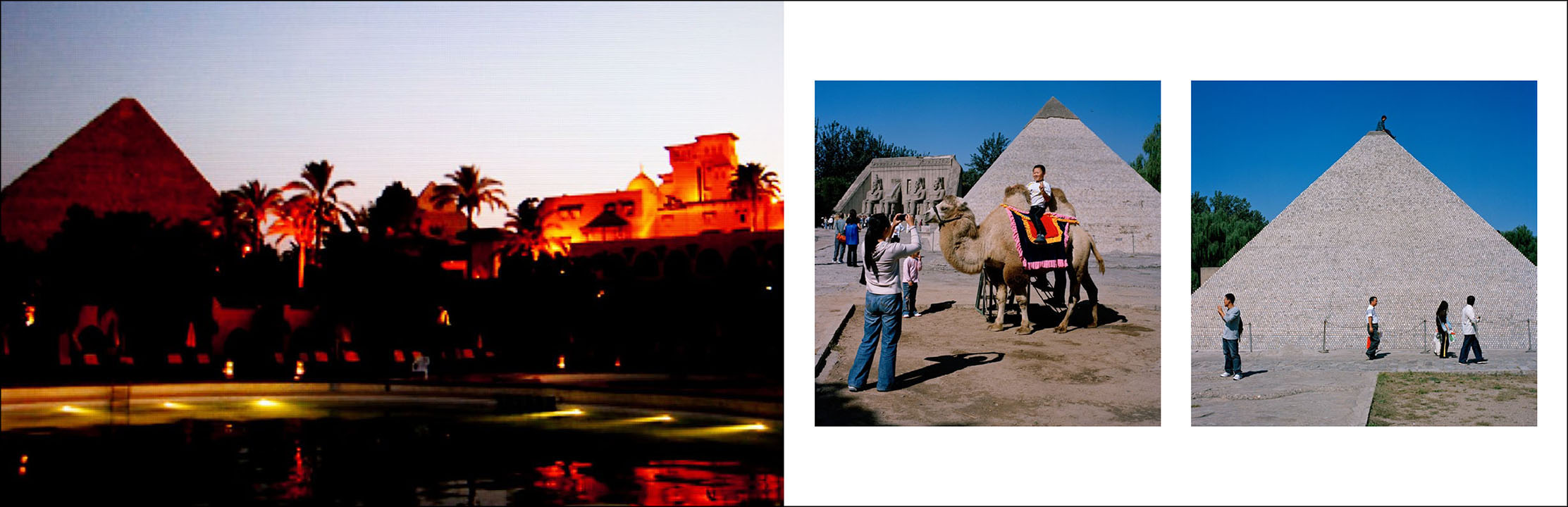

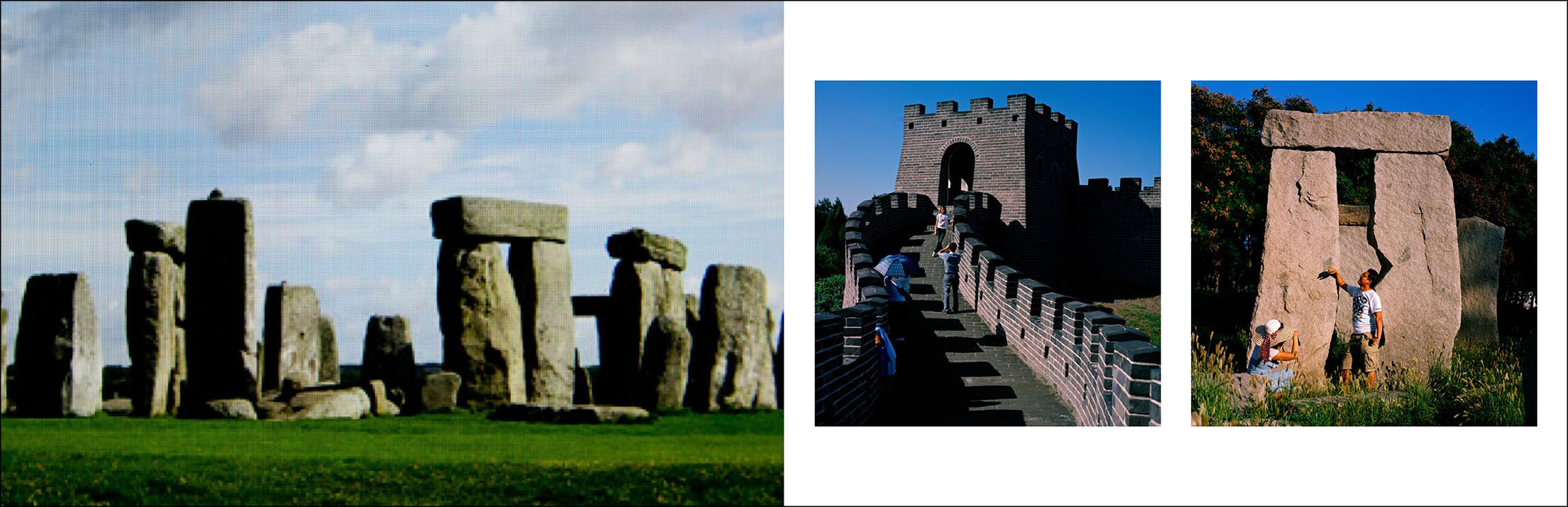

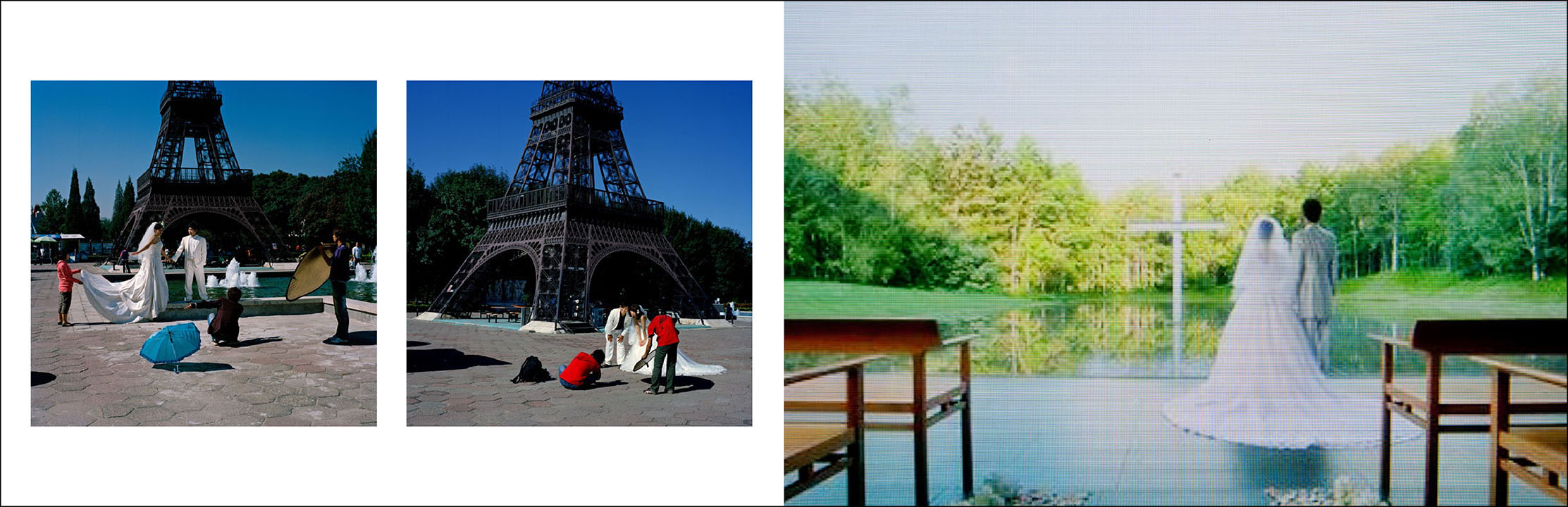

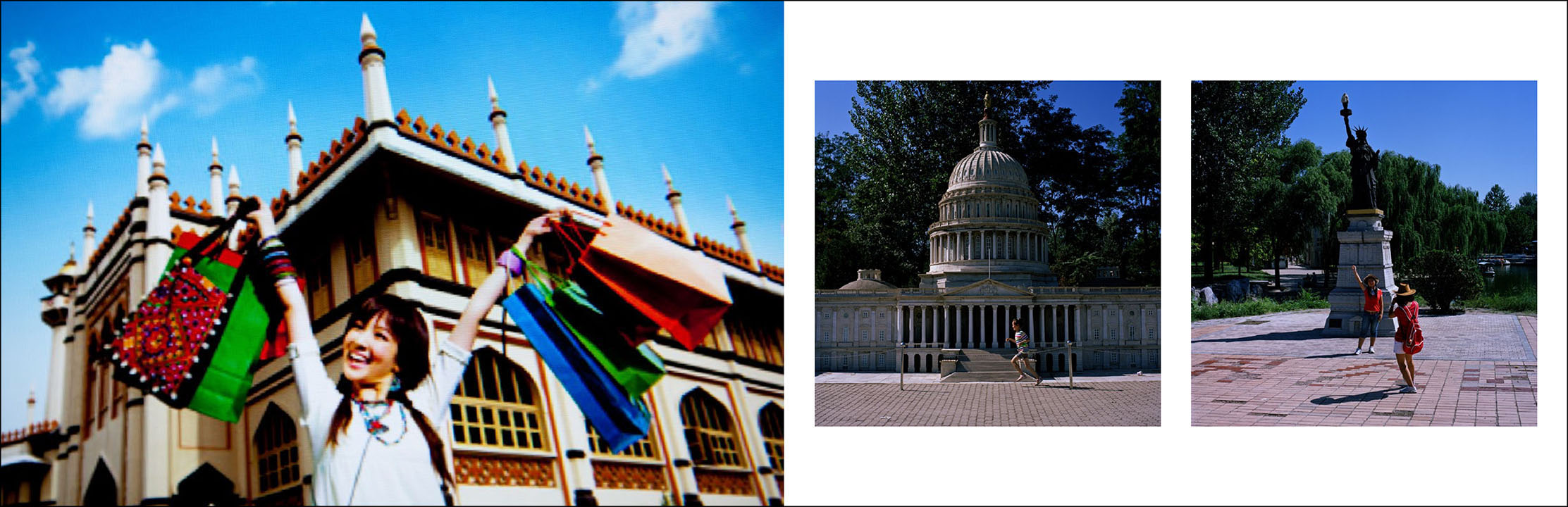

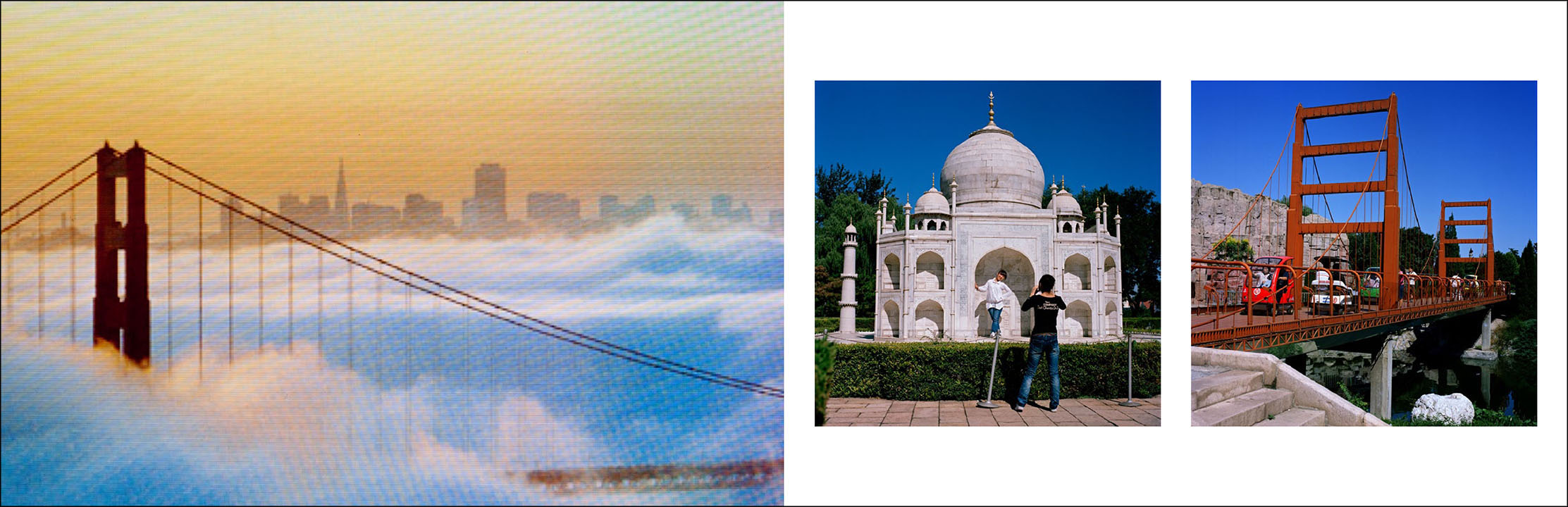

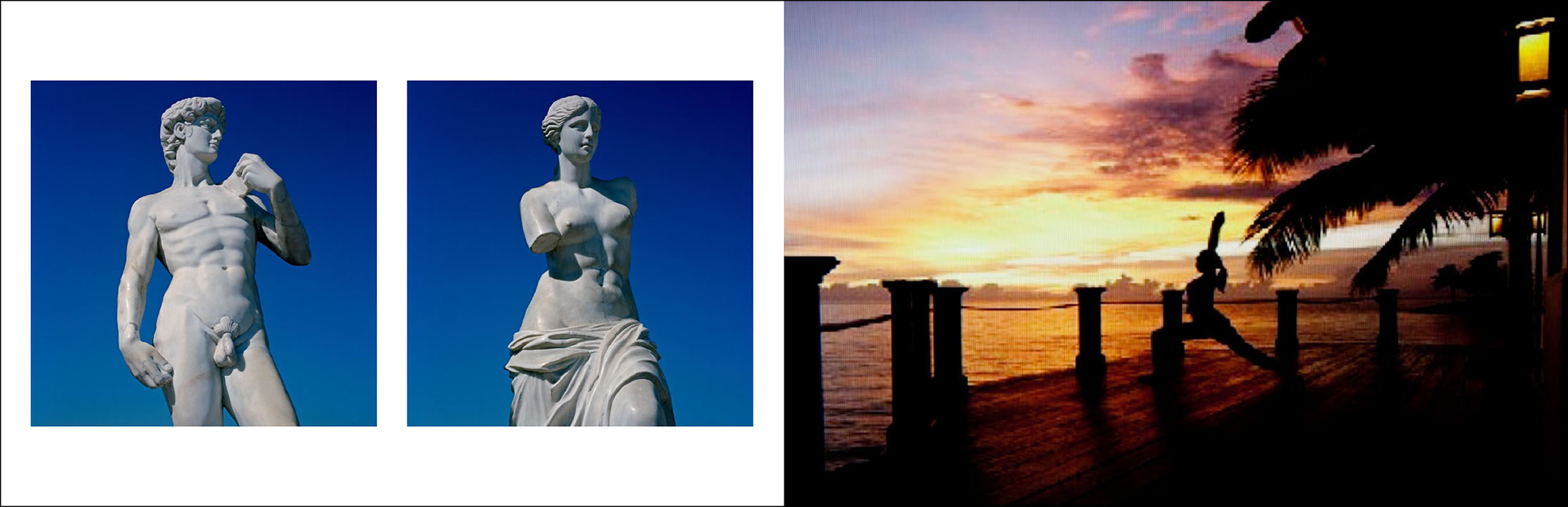

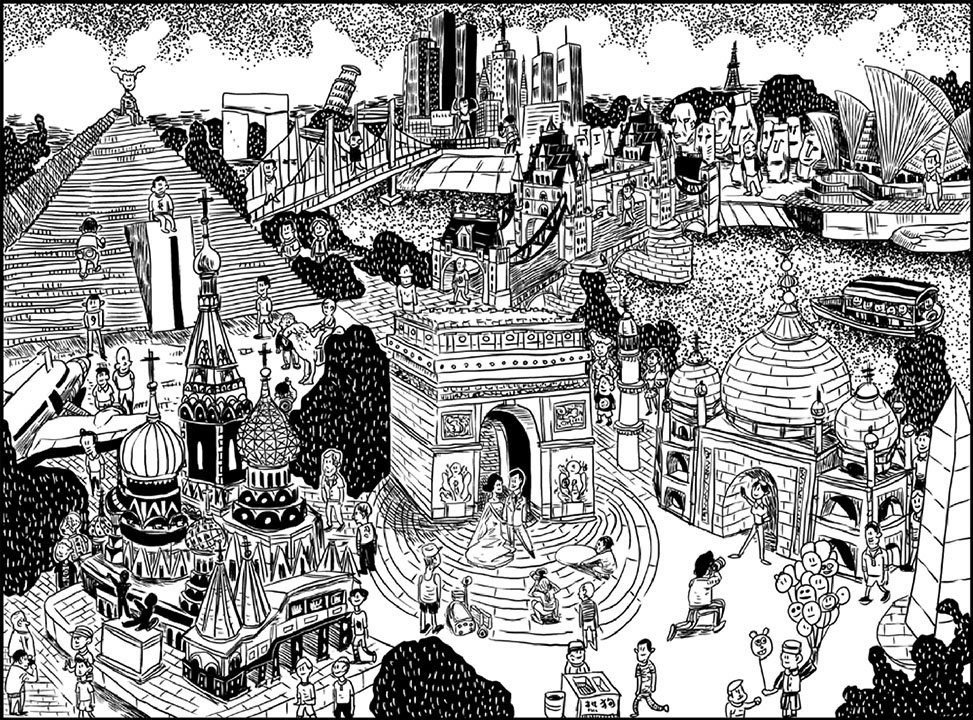

The ambitions of the nouveau riche occupying luxury apartments across Beijing also include international vacations and other such leisurely pursuits. A well-used passport is a sure sign of fulfilling a “modern” and “cultured” lifestyle and completes a trifecta along with home and car ownership. Even after the 2008 global economic downturn, China maintained the fastest growing outbound tourism market in the world. In 2009, the average expenses paid by Chinese for international travel went up 21% and will continue to grow as more and more flex their purchasing muscle. Luxurious departments stores in Paris such as Galeries Lafayette and Au Printemps now rely on Chinese tourists for a large chunk of their revenues and staff their boutiques with Chinese-speaking attendants to facilitate larger purchases. Meanwhile, a favorite local travel destination is the Beijing World Park. Tucked into the southwestern corner of the city, the Beijing World Park boasts over a hundred small-scale replicas of famous monuments and buildings from all over the world. Every year it still receives a healthy number of patrons including wedding photographers plying their trade in front of iconic romantic landmarks. Here Chinese can fantasize about visiting foreign countries and practice taking tourist snapshots. Most patrons also enjoy renting out “native” costumes and posing in front of the replicas. This is the same make-believe space that people embrace in Ikea’s faux showrooms and on the pristine leather seats of cars at the Beijing International Automotive Exhibition. It is a space of indoctrination, pushing a new consumer agenda, and a selling point for a notion of civility that will most likely prove as empty as other social movements in China’s past. These theatrical encounters are paired with photographs of the websites that peddle the majority of package vacations in China. It is a massive industry full of disinformation and fantastical imagery that will soon dominate the international travel market. Despite its increasing clout, China can perhaps still be characterized as the “sick man of Asia” with people across the country looking to Beijing to guide them into the new century. The seed of this malady no longer sprouts from China’s inability to defend itself militarily, as was the case last century, but from a vision of modernity that is simply improvident. The socioeconomic transformations occurring in China are detrimental to the environment and limited natural resources. It is impossible to ignore how a billion people plan to live in new cities and travel around the world. A reevaluation is in order of what it means to live a truly “harmonious” lifestyle in the largest and fastest developing country on the planet.